This e-book was written by Peter S. Kimmel, Publisher of FMLink. Its goal is to help building and facilities managers get their buildings back to the “new normal” occupancy and functioning safely for their occupants. It is written in four parts that are being published simultaneously; each links to the others. If you prefer to read a PDF, you may download the e-book here. Footnotes are at the end of each part; a full bibliography is available in the PDF.

PART THREE: Detailed considerations for key aspects of the facility and plan

The ultrastructural morphology exhibited by coronaviruses. The spikes that adorn the outer surface of the virus impart the look of a corona surrounding the virion. Image created at CDC.

In PART TWO, many concepts and ideas were surfaced. Some will apply to certain facilities, while others will not. There are several of these that would benefit from further elaboration, and they are discussed in more depth here in PART THREE:

- Floor layouts and circulation. Social distancing will dictate many changes to the workspace layouts and to how people use circulation space (aisles and hallways).

- Cleaning. Cleaning and disinfecting may be the largest concern of many staff, after making sure they maintain a safe distance from anyone with COVID-19.

- HVAC. Clean air may be assumed, but it is something the facilities manager must be sure to provide.

- New rules and guidelines. Many rules and guidelines were described in PART TWO. We attempt to summarize them here.

- Working from home. Until the lockdown ends, most will be working from home; after it ends, many likely will still be doing it. There are very special requirements here, for workers to remain productive.

- Implementing safe workplace controls and minimizing worker exposure risks. This is a summary of the OSHA guidelines that impact facilities.

Floor layouts and circulation

Modifying the floor layouts and circulation may be the most challenging problem of all:

- Many fewer workers will be able to fit in the workspace, which means a solution will be needed for the remainder.

- With fewer workers present, teams may not be able to stay intact, impacting productivity.

- The physical changes to the workplace will take time to design, money to purchase new furnishings, and time to wait for them to arrive.

- The ultimate solution (design) will need to work not only while social distancing is a concern, but will need to work after the pandemic subsides, so the whole space will not have to be redesigned again.

Steelcase’s Navigating What’s Next[1] makes the excellent point that the dominant characteristics of the pre-COVID workplace were designed to support “high levels of human interaction to fuel creativity, innovation, speed and agility.” These very same attributes pose challenges for what we will face next. According to Steelcase, the pre-COVID workplace includes:

- Open plan

- High density

- Shared spaces

- High mobility (to encourage people to move freely around the workplace)

- Communal spaces

Surely, much of this will need to change—in fact, these principles may even be considered the opposite of the post-coronavirus workplace. In the areas where today’s workplace is composed primarily of open plan, it likely will benefit from professional interior design—a service that may need to be contracted out. If so, there is no time like the present to start looking for a solution. This will not be easy and will take time, not only to find the designers, but perhaps to order furnishings and get them installed. And, since the coronavirus probably was not considered when developing the 2020 budget, there will need to be approval for any related expenditures as well.

A new layout will be imperative for every open office space, and some enclosed ones, especially those with two or more workers. Six-foot spacing will render many open office layouts untenable.

- One less expensive and more of a short-term interim open office solution will be to leave every other workstation empty, as in a checkerboard; of course, if the workspace were fully occupied pre-COVID, then many will still need to work remotely, either in coworking satellite space or in their homes.

- Another interim solution is to place moveable screens or file cabinets between workstations; while these are not necessarily attractive and can seem claustrophobic, they will be safe.

- Many other aspects of the office will need to be modified—even in-boxes are affected: these should be located at least 6 feet from a workstation’s occupant.

Any new layout should be easy to clean. Workers should leave their worksurfaces empty at the end of the day so they can be disinfected daily. If new furnishings will be obtained, they, too, should be very easy to clean and disinfect; where appropriate, they should be pre-treated with anti-microbial coatings.

Layouts should be easy to reconfigure not only for when needs change, but because of your FM team’s post-occupancy evaluation of what arrangements are working best for the occupants (and which need to be modified). Also, what works best for one type of group may not work best for another. All layouts must consider the needs for connectivity—both electrical and to the internet. Steelcase identifies three key strategies to reconfiguring the workspace:

- Density (space utilization rate)

- Geometry (how the furniture is arranged)

- Division (use of barriers and screens)

Immediately, as the office becomes reoccupied, to preserve-social distancing requirements, there will be fewer workers at one time. All workstations without barriers or screens between them will need to be reconfigured. Workers should never be facing one another without a barrier. If a workstation is shared by having multiple shifts, rules will need to be established about how to sanitize the workspace upon leaving, and places to store sanitary supplies will have to be designated for the general office workplace. Signage and stick-on decals can be used to keep workers separated and define preferred circulation routes.

There are now devices that can identify where each worker is at any point in time (through wi-fi and Bluetooth technology); these are implemented often through phone apps. Although the technology has been available for a few years, it has not been widely accepted because of privacy concerns; often, where it has been used, it has been in “anonymous” mode so the facilities manager can see where people are (in terms of density), but not exactly who was where. Now, this technology may need to be used in non-anonymous mode for contact-tracing purposes; that way, should someone be identified with the virus, it will be known who has been in contact with that individual for that and the preceding days. If such a device is used, regular evaluations of the data should be scheduled to see if certain building areas are prone to traffic congestion and what can be done to alleviate the congestion.

RXR Realty[2], a developer and property manager, is developing a social distancing app that measures how far away you are from others and then gives you a score at the end of the day. Those who keep over six feet away most of the time get the best scores.

Cushman & Wakefield developed “The Six Feet Office[3]” to help ensure safe social distancing. To understand the concept, imagine a 6-foot-radius circle embedded in the carpet, centered at one’s seat at a workstation. No one should be allowed to enter this space when the chair is occupied. Aisles and circulation must be outside of this area. Travel should be clockwise around the office, so people don’t pass each other too closely when they are going in opposite directions. Regardless of the specific solution for your office space, it will need to be thought through in advance.

Any new planning should try to incorporate the use of sensors to eliminate high-touch areas as much as possible. This could be sensors to open doors, turn on lights, open shades, elevator controls, and more. Some of these will be activated by sensing weight (floor sensors), sensing light pattern changes, or even by using phone apps to control items in individual workstations or get one through security.

Rules will be needed for potential areas of congregation such as breakrooms, as well as where copiers are located. Some of these spaces may need to be removed if it is determined that workers likely will not obey the distancing or no-touch rules. Similarly, you may need to reduce capacity of large meeting rooms by removing some of the seating; rules for how to enter and exit conference and meeting rooms will need to be established (so people don’t get too close to one another). Large meeting rooms may need to be repurposed as office space.

As the workplace starts its interim solution (likely the checkerboard pattern with fewer staff), designers will need to be reconfiguring the layout for what comes next. Some different furnishings likely will need to be ordered. This will result in a workable solution that is much more effective than the checkerboard. What happens after that will be determined by ongoing evaluations of what is working and not in the new layout.

Cleaning and disinfecting

Cleaning and disinfecting serve three purposes:

- Ensuring that the facility is safe, avoiding spread of the virus.

- Communicating to staff and visitors that management values their safety with paramount importance.

- Helping staff (and their families) to feel that the workplace is very safe.

Procedures must be developed to communicate an emergency to the cleaning staff. Emergencies are those that relate to the clean-up and disinfecting of an area that may have been contaminated by the coronavirus. Include disposal instructions for materials used for the cleaning.

Cleaning staff should clean frequently touched surfaces at least once daily (and some more frequently if they get a lot of use) or if they are in high-traffic areas. These include all worksurfaces; chair arms; file drawer handles; doorknobs; lavatory faucets; card readers; elevator buttons; and railings (including escalator handrails). A schedule should be developed for which surfaces should be cleaned and how frequently. Consider posting when this was most recently done for spaces—this gives staff a good and safe feeling about the spaces they frequent. Provide instructions for disposal of items used in the cleaning.

Identify shared equipment through the facility and develop guidelines for using and cleaning it. Are gloves required? Should equipment be cleaned before or after each use? Have appropriate wipes nearby. Make sure the cleaning crew disinfects the equipment daily, including all buttons, handles, levers, and other surfaces that may be touched such as all shared copiers, printers, and other office equipment.

Similarly, rules should be developed for opening file drawers and other common storage areas. Gloves? Wipes?

Staff should disinfect their own mobile phones frequently. The cleaning crew should clean desktop phones in the general office areas and at the workstations frequently; the staff should clean their own desktop phones as well, as phones are among the most COVID-19 infected equipment. For mobile phones, staff can use wipes (be sure they’re OK to use on mobile phones), ultraviolet (UV) wands (you can wave your wand over several phones at once), or cases in which you can place your phone for 10 minutes while the UV light sanitizes it.

Place hand sanitizers wherever people will most likely be touching food with their hands and at all entrances to buildings and conference / meeting rooms. Restrooms must provide a way for patrons to open doors without having to touch handles.

Cafeterias should have special considerations in addition to the use of food guards. In a cafeteria, people may sanitize their hands as they enter, but then may pick up a serving utensil that others have touched, so they will need to sanitize again; and then they may touch their tables. Consider dispensing paper bags in the cafeteria so diners will have a place to put their masks instead of on the tables while they are eating. They also should be able to find a handwipe as they approach the table, so they can sterilize it before they sit down.

Be careful with where you place hand sanitizers, as they will take up space, can look unsightly, and can physically block circulation; for these reasons, at some point they should be integrated into the design so that they are easily visible and accessible, but without the negative aspects.

Instruct workers to clean the worksurfaces in their office areas each night so the cleaning staff can wipe them with disinfectant wipes. Workers should be given supplies to clean all their own equipment daily, including phones, touchscreens, keyboards, mice, etc. Workers should not let others use their equipment.

Always check with manufacturer before using wipes on any surface, especially equipment; some chemicals can stain or erode surfaces. For the virus, because it is believed to have a fatty structure, soap can be most effective as it breaks down the fat.

According to NIH (National Institutes of Health), scientists from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases’ (NIAID)[4] Montana facility at Rocky Mountain Laboratories, the virus was detectable:

- In aerosols for up to 3 hours.

- On copper for up to 4 hours.

- On cardboard for up to 24 hours.

- On plastic and stainless steel for up to 2 to 3 days.

Teknion, a furniture manufacturer, has created a cleaning guidelines page[5] that goes into detail about which products to use on which types of surfaces and fabrics. They include wood veneer, painted finishes, laminates, metal, glass, and aluminum.

HVAC

There are two key elements of the HVAC system that relate to reducing the spread of the coronavirus:

- The type of air filters used and frequency in which they are changed.

- The percentage of outside air that is pumped into the building.

ASHRAE has recently approved two statements regarding the transmissions of the coronavirus as it relates to the operation of HVAC systems during this pandemic:

“Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 through the air is sufficiently likely that airborne exposure to the virus should be controlled. Changes to building operations, including the operation of heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning systems, can reduce airborne exposures.

“Ventilation and filtration provided by heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning systems can reduce the airborne concentration of SARS-CoV-2 and thus the risk of transmission through the air. Unconditioned spaces can cause thermal stress to people that may be directly life threatening and that may also lower resistance to infection. In general, disabling of heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning systems is not a recommended measure to reduce the transmission of the virus.”

See ASHRAE and CDC in PART FOUR for more information about changing air filters and other aspects of HVAC maintenance related to the coronavirus.

Ensure that there is adequate ventilation in work areas (you may need to consult with an HVAC engineer). If there are fans (pedestal or hard-mounted) situated in the facility, make sure that air does not blow directly from one worker to another. Untreated spaces that personnel may enter must be avoided.

Rules and guidelines

This section consolidates most of the new rules and guidelines mentioned previously that should be considered. These are summarized here to make it easy for you to have everything in one place—more details for each are provided elsewhere in PARTS TWO and THREE.

Many of the rules and guidelines will be short-term until the risks from the coronavirus are insignificant; you may want others to remain indefinitely, either for safety purposes or general best practices.

We have tried to organize the rules and guidelines in a way similar to how many facilities management functions are organized.

Because all facilities are different, you will find that some rules and guidelines may not work well for your organization (for example, not feasible, or too costly)—these may be ignored. However, it would be beneficial to identify a different way to satisfy the rationale behind the rule or guideline.

Management and oversight

- Develop working objectives for Workplace Coordinator.

- Identify types and frequency of communication with groups both inside and outside of facilities management, including corporate and building workplace coordinators, health group, finance, and budget personnel.

- Prepare agenda for scheduling weekly meetings with the team to evaluate weekly procedures and determine which should be modified.

- Develop procedures to determine who should be allowed to telework, whether shifts and staggered work hours will be needed, and if so, how they should be implemented.

- Develop guidelines to determine which teleworkers should be eligible for which types of furnishings and equipment, and how they should be procured.

- Develop guidelines and criteria for evaluating actions taken so far and for what will be done next. Determine how to collect the information, e.g., surveys, observation, measuring data.

- Develop procedures for a quick shut-down of the facility should it be necessary.

Interior layout and space management

- Determine the principles for workstation layouts and circulation, to achieve social distancing.

- Develop guidelines for use of aisles and hallways (one-way traffic, passing others).

- Determine where to have queues and how to mark them, including 6’ social distancing; determine where stanchions are required.

- Identify where visitor-staff interactions are to take place.

- Create signage for new rules (room capacities, one-directional circulation, queuing).

- Develop or modify existing procedures to procure videoconferencing equipment and guidelines for how to reserve it (there will be much more demand for this than in the past).

- Review guidelines to secure temporary space, if needed.

Operations and maintenance

- Determine frequency for HEPA filter replacement.

- Determine frequency for cleaning heat transfer coils.

- Determine desired percentage of fresh air.

- Develop procedures and frequency for checking certain equipment and building systems for problems that may be occurring due to the lockdown or coronavirus.

Security

- Develop procedures for (touchless if possible) visitor and staff check-in (what needs to be checked).

- Develop procedures for shipping and receiving goods.

- Determine rules for queuing.

Janitorial

- Determine frequency of standard cleaning, including use of disinfectants (if different from before).

- Determine frequency of deep cleaning, including use of disinfectants (which objects).

- Develop procedures to dispose of cleaning materials that may have been exposed to the coronavirus.

- Develop procedures in the event of an emergency related to spread of coronavirus.

- Develop procedures for cleaning any amenities and other rooms that have been closed, both now and after they reopen.

Equipment and supplies

- Develop a list of supplies needed for cleaning and disinfecting (including wipes, sanitizer, shop towels, gloves, masks, disinfectants, soaps, detergents, and bleach).

- Develop a list of supplies needed to identify social distancing demarcations (floor/carpet tape, decals).

- Determine minimum inventory levels for each item; levels will be higher than pre-COVID-19.

- Determine how many HEPA filters to keep in stock; levels will be higher than pre-COVID-19.

Rules and guidelines for staff and visitors

These need to be communicated to all staff and visitors. Many of them will be written by the facilities group, sometimes in consultation with other groups. In many instances, signage will be helpful.

- Weekly newsletter to share building pandemic news, tips, statistics, and concerns.

- Procedures for receiving and using masks, sanitizing wipes and other supplies (visitors and staff).

- Procedures for temperature checks (when, where).

- Procedures for reporting symptoms of the coronavirus (for self, others).

- Procedures for using common equipment (copiers, printers, videoconferencing, etc.).

- Procedures for hoteling (if applicable).

- Identification of which rooms and facilities will be closed.

- Guidelines for use of workstations (sanitizing, visitors, cleaning after use, what to clean).

- Guidelines for use of meeting rooms (capacity, entering and exiting).

- Guidelines for use of cafeteria (capacity, hand sanitation, mask placement when eating, etc.).

- Guidelines for use of elevators and escalators, including queuing, elevator capacity, social distancing.

- Guidelines for use of amenities and special spaces (capacity, sanitizing instructions)—reception, fitness center, daycare center, break rooms.

- Guidelines for working from home and remote locations (teleworking).

- Guidelines for getting to the office (transportation, parking, alternatives).

- Social distancing in hallways and aisles.

- Social distancing guidelines (in workstations and other locations).

- Social distancing guidelines (in queues).

- Social distancing apps (if required).

- Density apps—showing number of people in a given area (if required).

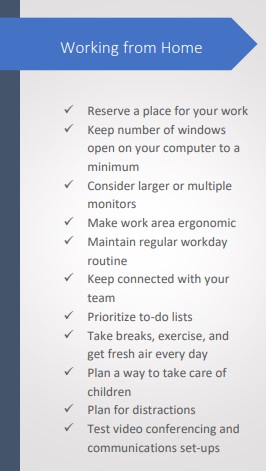

Working from home

According to the Harvard Business Review[6] (HBR), remote working employees face many challenges that they don’t face in the workplace, which can lead to declines in job performance, especially in the absence of appropriate training and guidance. The HBR article identifies some of the common challenges (presented here) and then offers guidance for ameliorating each:

According to the Harvard Business Review[6] (HBR), remote working employees face many challenges that they don’t face in the workplace, which can lead to declines in job performance, especially in the absence of appropriate training and guidance. The HBR article identifies some of the common challenges (presented here) and then offers guidance for ameliorating each:

- Lack of face-to-face supervision

- Lack of access to information

- Social isolation

- Distractions at home

We address many of the distractions and provide additional resource material below. The HBR goes into detail on how management can support remote employees, including one that ties directly to facilities managers:

- “Provide several different communication technology options.”

They go on to say that besides telephones and emails, include videoconferencing. See Communications Equipment and Videoconferencing below.

Work environment and habits

- Create a place reserved 100% for your work, which should include all equipment and supplies you will need, just as if you were in your office. Try to create a physical barrier between the workplace and the rest of your home, if possible, even if it is just a partial-height screen.

- If you have only one monitor, try to avoid having too many windows on it open at one time.

- If you’ll be spending a good part of your day on your computer, you will likely benefit from a larger monitor or perhaps two. These can be attached to your laptop through a docking station, which may also come in handy if you have two or more peripherals to plug into your laptop.

- Similarly, if you’ll be spending more than four hours at a computer, you will benefit from an ergonomic workstation at home. See the Ergonomic section below for more on this.

- Maintain a regular workday routine, including hours at “the office.”

- Stay connected with your team throughout the workday. It can get very frustrating if someone needs to reach you and can’t. If you leave your workspace, check your messages as soon as you return.

- Prioritizing your to-do tasks becomes more important than ever.

- For your own sanity and to keep a clear head, take breaks, and be careful not to overwork. And don’t forget to exercise and get fresh air daily. You will be more productive after that!

- If you have very young children, childcare is a must. For slightly older kids, try to explain (in a relaxed setting, not while they are interrupting a task of yours) that things will be different for a while as you work from home, and it will be something to which everyone (including you) will need to adjust. For very special (hopefully infrequent) times and only when necessary, have a signal to indicate, “Do not Disturb!”

- Besides kids, find a way to deal with distractions that don’t come up in the office, such as personal calls, doorbell ringing, etc. Sometimes, these cannot be avoided, and they can get worse if you don’t deal with them. Use your judgment, and if you need to take a break to deal with them, then allow make-up time later. There are lots of articles out there on the web with good advice. Try doing a search, for example, on “how to deal with family disruptions when working from home”—you’ll be amazed at what you come up with! For slightly different results, try searching on “how to deal with distractions when working from home.” Here are some of my favorites:

- https://www.bitqueues.com/here-is-how-you-can-manage-interruptions-when-working-from-home/

- https://www.moneycrashers.com/tips-increase-productivity-avoid-distractions-working-home/

- https://www.flexjobs.com/blog/post/dealing-with-distractions-working-from-home/

- https://zapier.com/blog/remote-work-challenges/

- https://www.themuse.com/advice/work-from-home-kids-coronavirus

Many of these websites have similar ideas, which reinforce how seriously they should be taken. They will determine how productive you will be.

- Agile Work Evolutions developed a Work@Home checklist[7] that addresses environment preparation, technology, communication protocols, training, meetings, and much more.

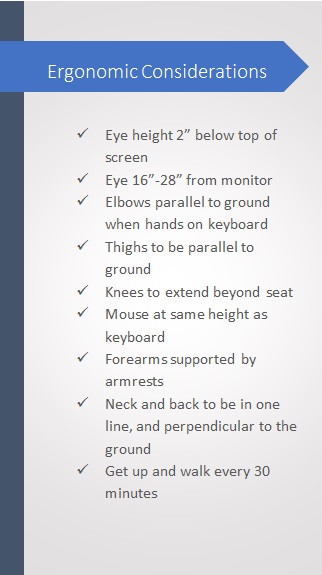

Ergonomics

If you will be spending a good part of your day at your computer, you need to be sure your workstation is configured properly. This will help you avoid back problems, carpal tunnel, eye and neck strain, and a host of other maladies. Here are some guidelines:

If you will be spending a good part of your day at your computer, you need to be sure your workstation is configured properly. This will help you avoid back problems, carpal tunnel, eye and neck strain, and a host of other maladies. Here are some guidelines:

- The eyes should be level with a horizontal line a few inches below the top of the screen, and at a distance between 16” to 28” from the screen.

- The elbows should be bent a bit more than 90 degrees when your hand is on the keyboard. If you will be at the computer a lot, you should adjust your worksurface height to be ideal for when you are using your keyboard (ideal writing surface height is usually a couple of inches higher)—you will need to decide if you will be spending more time writing or typing at your worksurface. Your keyboard should be at the same height as your elbow, which means that your wrist will be slightly bent.

- The seat height should allow your hips to be bent a bit more than 90 degrees when your feet are flat on the floor (which is where they should be when you are typing). It helps for your chair to have lumbar support.

- The back of your knees should be a bit over the front edge of the seat.

- Your mouse should be at the same height as the keyboard and just a few inches away from it.

- Your forearms should be supported by armrests.

- Keep your neck and back vertical and straight.

- Get up and take a break every 30 minutes or so.

There also are some good checklists available:

- The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has published Computer Workstation Ergonomics: Self-Assessment Checklist[8]. It has graphics to demonstrate all you need to know.

- The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has published a similar guide, Computer Workstations eTool[9], with a few more details, but without the graphics.

Communications equipment and videoconferencing

- Determine what equipment you need. Are the camera and your microphone on your laptop sufficient, or do you need a stand-alone webcam and microphone?

- Determine the software and applications you require and understand the limitations of each product you are considering. Some of the more popular ones are Skype, Zoom, Slack, Microsoft Teams, WebEx and GoToMeeting. Each has its strengths. Many organizations have their own favorites and guidelines as to which to use.

- Become very familiar with your equipment and software—don’t use them for the first time when you’re in a meeting.

- Learn how to mute your microphone, black out your camera, change the presenter, pause a presentation, share an application, hold a conference call (with or without cameras), etc. Also, learn how to turn a phone call into a video meeting, should the need arise.

Looking good in front of a camera

- The first requirement is to place your set-up in the proper environment. The best backdrop is often a plain, white background. There should be some distance between you and the wall, so you avoid distracting shadows. Another favorite backdrop are bookshelves. “Neutral” is good; avoid strong design elements—while some may like your taste, others may find it distracting. Clutter is not only distracting but can reflect negatively on you. Check out what others are doing in their live chats. If you still need to be convinced of the value of the above guidelines, remember that there are some viewers who will focus as much attention on your home as on what you have to say—when I once asked someone what they thought of a chat I had missed, the first few minutes of response were all about the kind of home the person had! I am sure that is not what the speaker had intended.

- Lighting is also important. Be sure your face is properly illuminated (a luminaire a couple of feet from your face is ideal) and avoid shadows—LEDs and fluorescents are best for that. Be sure there is no bright source shining toward you in the camera lens, and that includes a window in the daytime—backlighting will make your head read as one giant shadow.

- There’s more than one way to put your face in the proper light. Besides the lighting, people’s heads look best when the camera is slightly above one’s eyes. This can present a problem with a laptop’s camera, but it is easily resolved by propping the laptop up on some books. And do look into the camera—that’s another way of saying, “Look someone in the eye.”

- Because cameras don’t have the range of contrasts that the human eye does, you will look better if you’re not wearing a shirt/blouse that it very dark or very light. It is always a good idea to check out your setup in advance of a call, and that includes what you may be wearing.

- Be careful of a room that has primarily hard surfaces—these reflect sound and can produce an unwanted echo. Also, many laptop microphones are not of sufficient quality to make your voice as clear as it needs to be; avoid speakerphones. It’s much better to have a dedicated microphone or at least a set of good earbuds.

- Keep the camera steady. This can be especially a problem with a laptop as the camera source unless the laptop is on a solid surface (not your lap!). And even then, if it were to move, such as when you’re typing on the keyboard, your presentation will become a disaster.

- Be sure you’re not sharing your whole screen unless you really intend to do so. Otherwise, just ID the applications you wish to share.

- Plan ahead for surprises, such as what to do if one of your kids enters the room, your dog jumps on your lap, another phone rings, etc. Since many are working from home, it’s best to be prepared and take precautions so these interruptions don’t happen; but if they do, it’s preferred to use the interruption as an opportunity for a lighter moment rather than becoming annoyed with the distraction. Everyone on the call knows everyone else is working from home, so they will understand that these things can happen.

Creating safe workplaces and minimizing worker exposure risks

The guidelines in this section are from OSHA’s Guidance on Preparing Workplaces for COVID-19[10]. They first identify the types of controls available to protect workers:

- Those that physically isolate employees (engineering controls)

- Those that require the individual to “do” something (administrative controls)

- Those that require use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

In the second portion below, the guide describes the types of exposure and risk (high, medium, low). Finally, it applies additional controls to the higher risk exposures.

Types of controls to protect workers

Engineering controls

The most effective controls, according to OSHA, are known as engineering controls, which involve isolating employees from work-related hazards; these controls do not rely on worker behavior and can be very cost-effective to implement. They include:

- High-efficiency air filters

- Increased ventilation rates

- Physical barriers, such as plastic sneeze guards

- Drive-through windows for customer service

- Specialized negative pressure in locations that are prone to airborne infections

Administrative controls

Administrative controls require action by the worker or employee, and typically involve changes in work policy or procedures. They try to minimize exposure to a hazard. Because their success is dependent on employee vigilance and compliance, they are not as effective as engineering controls. Administrative controls include:

- Encouraging sick workers to stay at home

- Minimizing contact through increasing virtual communications and telework where possible

- Reducing employees working at the same time by increasing shifts or establishing alternating days

- Discontinuing non-essential travel, especially to places where there may be large outbreaks

- Developing emergency communications plans and internet-based worker forums

- Offering workers education and training on virus risk factors and protective behaviors

- Training workers who require protective clothing and equipment

Safe work practices

These are administrative controls that include procedures for safe and proper work and tend to reduce the exposure to a hazard. Examples include:

- Providing resources that promote personal hygiene, such as: tissues, no-touch trash cans, hand soap, alcohol-based wipes and hand rubs containing at least 60% alcohol, disinfectants, and disposable towels for cleaning work surfaces

- Requiring regular hand washing or use of alcohol rubs, and always after the hands are visibly soiled or after removing PPE from your face

- Posting of handwashing-reminder signs in restrooms

Personal protective equipment (PPE)

Use of PPE does not replace the above prevention strategies, as it is not as effective. All PPE must be properly fitted for each worker, and regularly inspected and maintained. Workers who work within 6 feet of people known to be or suspected of being infected with the coronavirus need to use proper respirators, such as N95s. Examples include:

- Gloves

- Goggles

- Face masks and shields

- Respiratory protection

Types of exposure risk

The use of the above controls will vary depending on the worker’s risk level to exposure. OSHA has divided these into four levels: Very High, High, Medium, and Lower Risk. Most workers are classified as Lower Risk, followed by Medium, and then High, and the least amount as Very High. Some examples are offered for each type of exposure risk (many of the higher risk workers are in healthcare):

Very high exposure risk

- Healthcare workers performing aerosol-generating procedures on known or suspected COVID-19 patients

- Healthcare and laboratory personnel collecting or handling specimens from known or suspected COVID-19 patients

- Morgue workers performing autopsies on the bodies of people who are known or suspected of having COVID-19 at the time of their death

High exposure risk

- Healthcare delivery and support staff exposed to known or suspected COVID-19 patients

- Medical transport workers moving known or suspected COVID-19 patients in enclosed vehicles

- Mortuary workers involved in preparing the bodies of people known to have or suspected of having COVID-19 at the time of their death

Medium exposure risk

These are workers whose jobs require frequent and/or close contact with people who may be infected with the coronavirus, but who are not known or suspected COVID-19 patients, such as travelers who return from international travel or areas where there is ongoing community transmission.

Lower exposure risk

These are jobs that do not require contact with people known to be or suspected of being infected with the coronavirus, nor frequent close contact with the general public.

Additional controls for each exposure risk

Each of these types of risks may require certain additional controls, beyond those mentioned above. Each will be discussed below, beginning with those at least risk:

Controls for workers with low exposure risk

Engineering controls

- No additional controls are recommended; not all controls may be applicable for all situations.

Administrative controls

- Monitor public health communications about COVID-19.

- Regularly check the CDC COVID-19 website.

Personal protective equipment

- No additional PPE is recommended.

Controls for workers with medium exposure risk

Engineering controls

- Install physical barriers where feasible.

Administrative controls

- Consider offering face masks to ill workers to contain respiratory secretions until they leave the workplace.

- Keep customers informed about COVID-19 and ask sick customers to minimize contact with workers.

- Minimize customer face-to-face contact with workers.

Personal protective equipment

- Each employer should select the combination of PPE that protects workers specific to their workplace.

- Workers may need to wear some combination of gloves, gown, face mask and/or a face shield, or goggles.

Controls for workers with high or very high exposure risk

Engineering controls

- Ensure appropriate air-handling systems are installed and maintained. See the CDC’s Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Healthcare Facilities[11].

- Place known or suspected COVID-19 patients in an airborne infection isolation room.

Administrative controls

- None of these are related to facilities managers

Personal protective equipment

- Workers will likely need to wear some combination of gloves, gown, face mask and/or a face shield, or goggles.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 4 | Go to top ↑

[1] STEELCASE

Steelcase. (2020). Steelcase: Navigating What’s Next [Ebook]. Retrieved from https://info.steelcase.com/hubfs/Steelcase_ThePostCOVIDWorkplace.pdf

[2] RXR REALTY

RXR REALTY. (2020). RXR Realty. Retrieved 10 May 2020, from https://rxrrealty.com/

[3] CUSHMAN & WAKEFIELD

Cushman & Wakefield. (2020). 6 Feet Office | Designing new office spaces to respond to COVID-19 | Netherlands | Cushman & Wakefield. Retrieved 9 May 2020, from https://www.cushmanwakefield.com/en/netherlands/six-feet-office

[4] NIH / NIAID

NIH / NIAID. (2020). New Coronavirus Stable for Hours on Surfaces. Retrieved 9 May 2020, from https://www.niaid.nih.gov/news-events/new-coronavirus-stable-hours-surfaces

[5] TEKNION

Teknion. (2020). Fabrics & Finishes Cleaning Guidelines. Retrieved 9 May 2020, from https://www.teknion.com/fabrics-and-finishes-cleaning-guidelines

[6] HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW

Harvard Business Review, Larson, B., Vroman, S., & Makarius, E. (2020). A Guide to Managing Your (Newly) Remote Workers. Retrieved 9 May 2020, from https://hbr.org/2020/03/a-guide-to-managing-your-newly-remote-workers?ab=hero-subleft-3

[7] AGILE WORK EVOLUTIONS

Agile Work Evolutions. (2020). Work@Home Checklist for Employers [Ebook]. Agile Work Evolutions. Retrieved from https://agileworkevolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/Work@Home-Checklist-for-Employers-EN-FR.pdf

[8] NIH

NIH. (2020). Computer Workstation Ergonomics: Self-Assessment Checklist [Ebook]. NIH. Retrieved from https://www.ors.od.nih.gov/sr/dohs/Documents/Computer Workstation Ergonomics Self Assessment Checklist.pdf

[9] OSHA

OSHA. (2020). Computer Workstations eTool. Retrieved 9 May 2020, from https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/etools/computerworkstations/checklist_evaluation.html

[10] OSHA

OSHA. (2020). Guidance on Preparing Workplaces for COVID-19 [Ebook]. OSHA. Retrieved from https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3990.pdf

[11] CDC

CDC. (2020). Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities: Recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Retrieved 9 May 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5210a1.htm

To download the book, please click here.

To contact Peter Kimmel, the author, please email peterk@fmlink.com.

About the author

Peter Kimmel, AIA, IFMA Fellow, a former facilities manager, is the founding publisher of FMLink, the information-based online magazine for facilities managers (https://fmlink.com). He also is a Principal of FM BENCHMARKING, the online benchmarking service for facilities managers (http://fmbenchmarking.com).

Prior to founding FMLink in 1995, Peter was president of his own FM consulting firm for more than ten years, focusing on helping FMs automate their facility operations and develop strategic facility plans. Before that, he managed facilities in the Federal government and in the private sector for over ten years, including the development of federal policies and programs.

Peter speaks at a variety of conferences, and his writings have been published in most FM magazines. He is a six-time winner of the International Facility Management Association’s (IFMA’s) Distinguished Author Award (most recently in 2020 for this e-book); besides this 2020 award, he is particularly proud of his 2014 e-book on benchmarking, which was commissioned by the IFMA Foundation. He also was the founding President of IFMA’s Capital Chapter. IFMA has honored Peter with its award for Distinguished Service, and in 1997, he was named an IFMA Fellow.

Peter is a registered architect and holds a Master of Architecture degree from the University of California.