by Brianna Crandall — September 14, 2016 — Despite their close economic, social and cultural ties, Canada and the United States face different challenges to reducing GHG emissions and are employing different approaches in their respective climate policies, according to a new report by IHS Markit, a global provider of critical information, analytics and solutions.

While the two countries have chosen similar greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction goals, differences in the nature of their economies and emissions sources are reflected in their climate policies. Policy efforts in the United States are primarily focused on specific sectors, whereas in Canada more effort is now being placed on pricing carbon, finds IHS.

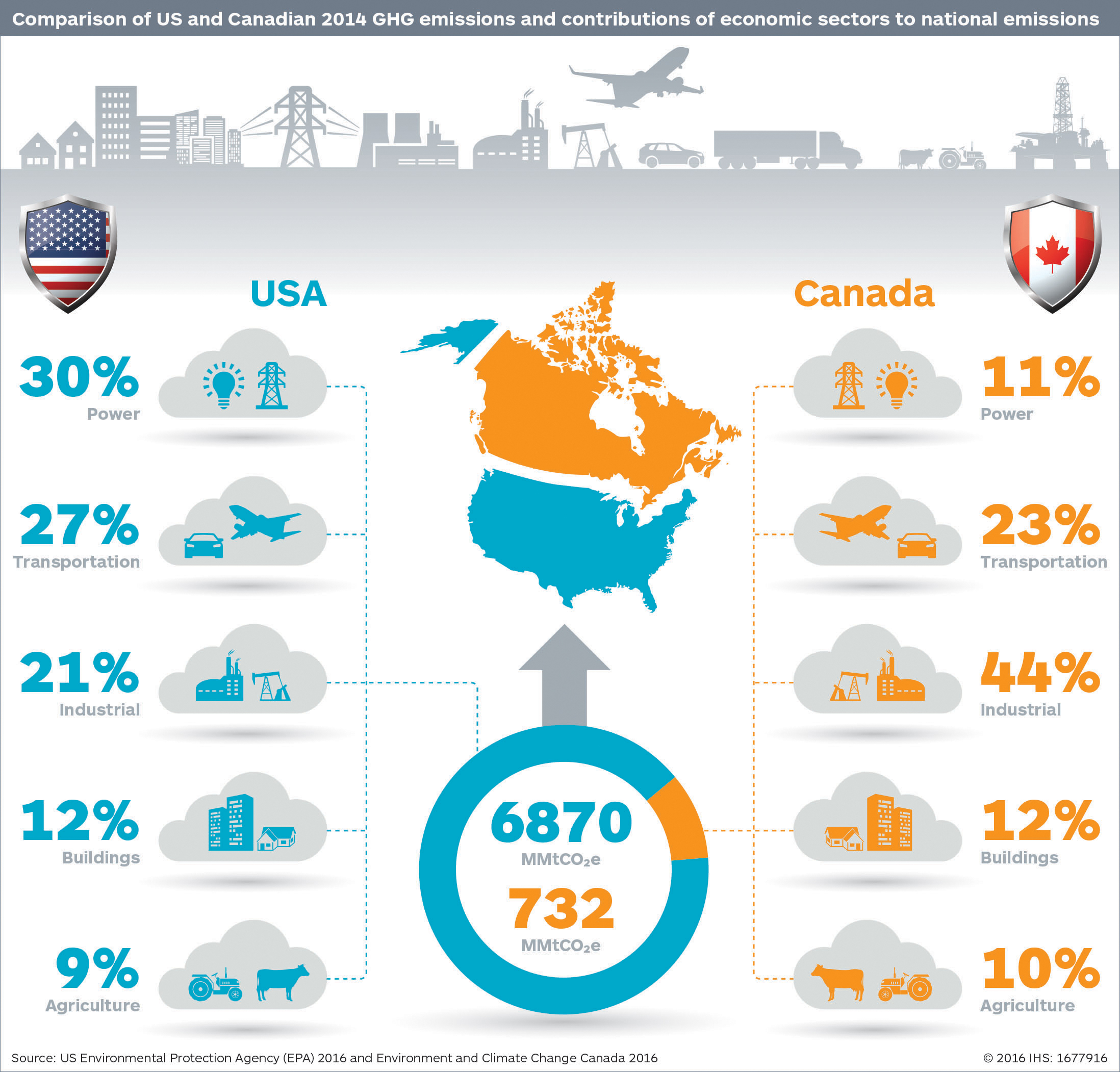

Comparison of U.S. and Canadian 2014 GHG emissions and contributions of economic sectors to national emissions (Click to enlarge)

The report, titled The State of Canada and U.S. Climate Policy, was produced by the IHS Oil Sands Dialogue. It reviews the GHG emissions profiles of both countries and the state of their current climate policies.

Kevin Birn, director for IHS Energy and head of the IHS Oil Sands Dialogue, comments:

How to address climate change has become a defining question of the 21st century, and there has been increased policy momentum in both Canada and the United States over the past year. While the two countries maintain similar policy approaches in several areas, the reality is that each country is also starting to develop its own distinct climate policy portfolio based on the specific attributes of its economies and GHG emissions profiles. There is not a one-size-fits-all approach to reducing emissions.

Differences in the makeup of the countries’ respective power sectors are a primary example of where their approaches diverge.

U.S. electric power generation — particularly from coal — is the country’s single largest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter, accounting for 30 percent of U.S. total emissions. Access to abundant and affordable shale gas (which emits half the amount of GHG compared to coal) and the declining cost of renewables provide the United States with a relatively low-cost opportunity to reduce power sector, and thus national, emissions.

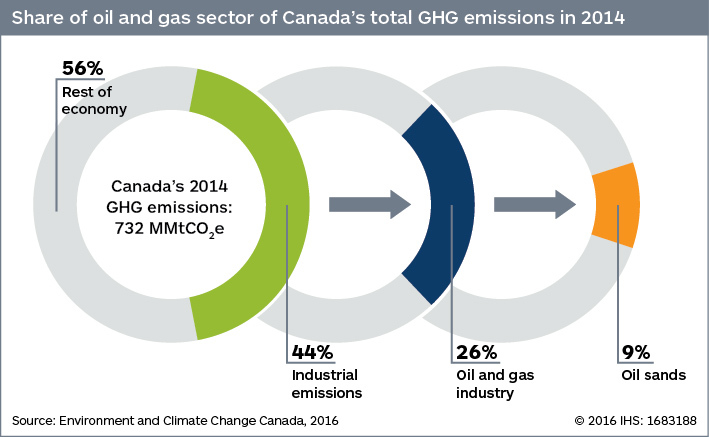

In contrast, about 80 percent of Canada’s power generation sector is already zero-emitting, mainly due to the high share of hydroelectric power. The industrial sector is Canada’s single largest emitter, representing 44 percent of total emissions. This sector includes oil and gas production and refining, which account for 26 percent of Canada’s total emissions.

The Canadian oil sands, which have been the subject of heightened interest due to their relatively higher GHG intensity compared to some other crude types, represent 9 percent of the country’s emissions. However, the government of Alberta has instituted a cap on emissions — limiting future GHG emissions growth from the oil sands.

In absence of an emissions-intensive power sector, Canada is looking elsewhere to reduce GHG emissions, the report says. Various models of carbon pricing are advancing across Canada. The federal government has announced its intention to implement a harmonized pan-Canadian price for carbon by the end of this year. Separately, various carbon-pricing mechanisms at the provincial level could cover up to two-thirds of Canada’s total emissions in 2017, the report says.

The move towards carbon pricing provides a unique set of challenges for Canada, which historically has sought to align its policies closely with the United States (its largest trading partner) over concerns that unilateral action could hinder industrial competiveness, the report says.

This contrasts with regulation focused on electrical power generation, for instance, which is more insulated from competitiveness concerns because of technical and economic limitations to large-scale power transmission.

Hossein Safaei, associate director for IHS Energy, points out:

Unilateral climate policy can add costs to domestic export-dependent firms that their competitors may not face. Firms that compete globally may physically relocate or lose out to their competitors. This weighs heavily given Canada’s close trading relationship with the United States and its large oil and gas sector which competes globally and with U.S. firms for investment, labor and markets.

IHS Canadian Oil Sands Dialogue research is available on the IHS Web site. The State of Canada and U.S. Climate Policy is available for free download from the IHS Web site upon registration.