Submitted by Ware Malcomb

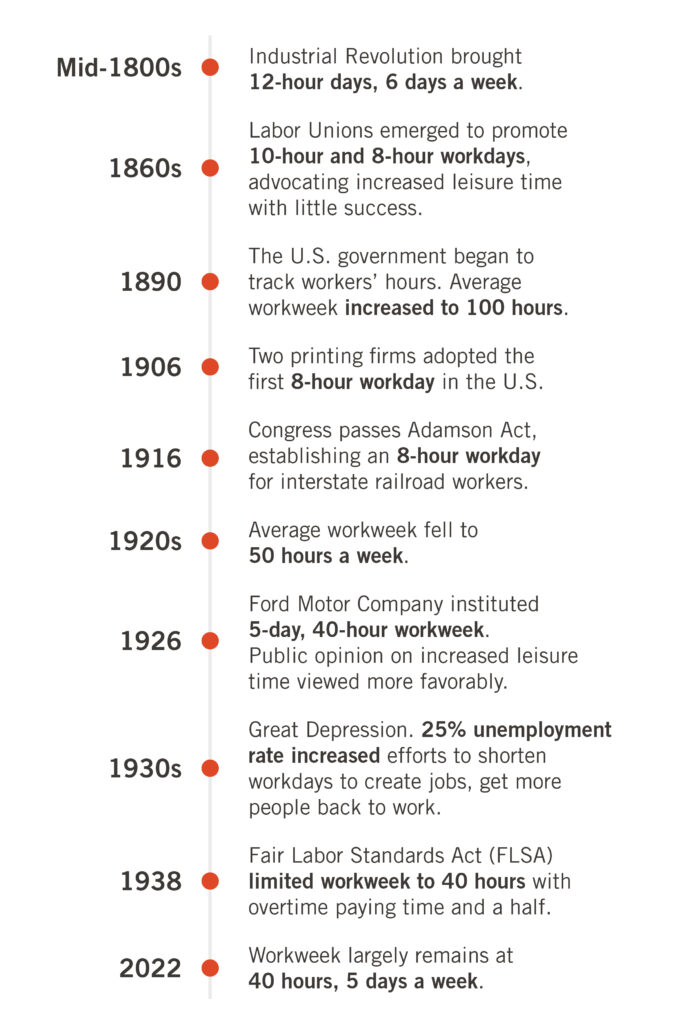

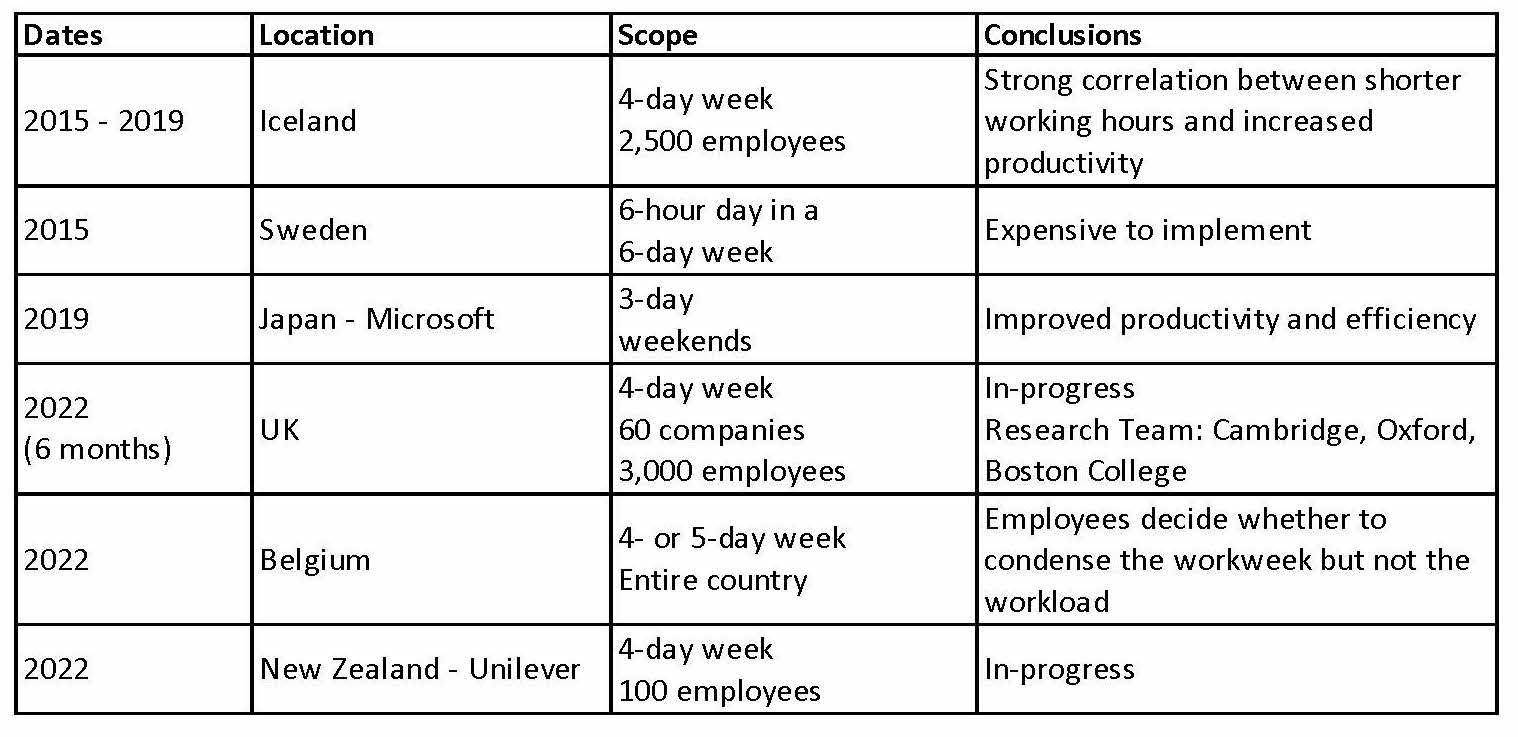

By Cynthia Milota, Director, Workplace Strategy, and Jonathan Wells, SHRM-SCP, Senior HR Specialist – Ware Malcomb — In the workplace, the past three years have brought renewed focus to work/life balance, flexible work time and the length of the work week. Following the lead of shortened workweek trials from Iceland to New Zealand, the U.K. has also undertaken a four-day workweek experiment.

Across countries and industries, emerging discussions not only consider how many days to require in the office, but also how many workdays to require in the week. Covid not only disrupted the consensus about how and where employees work best and most efficiently, it also prompted a shift in employee expectations for the workplace experience.

What if the question should not be the days of work in a week or the days in the office, but rather the experience in the workplace?

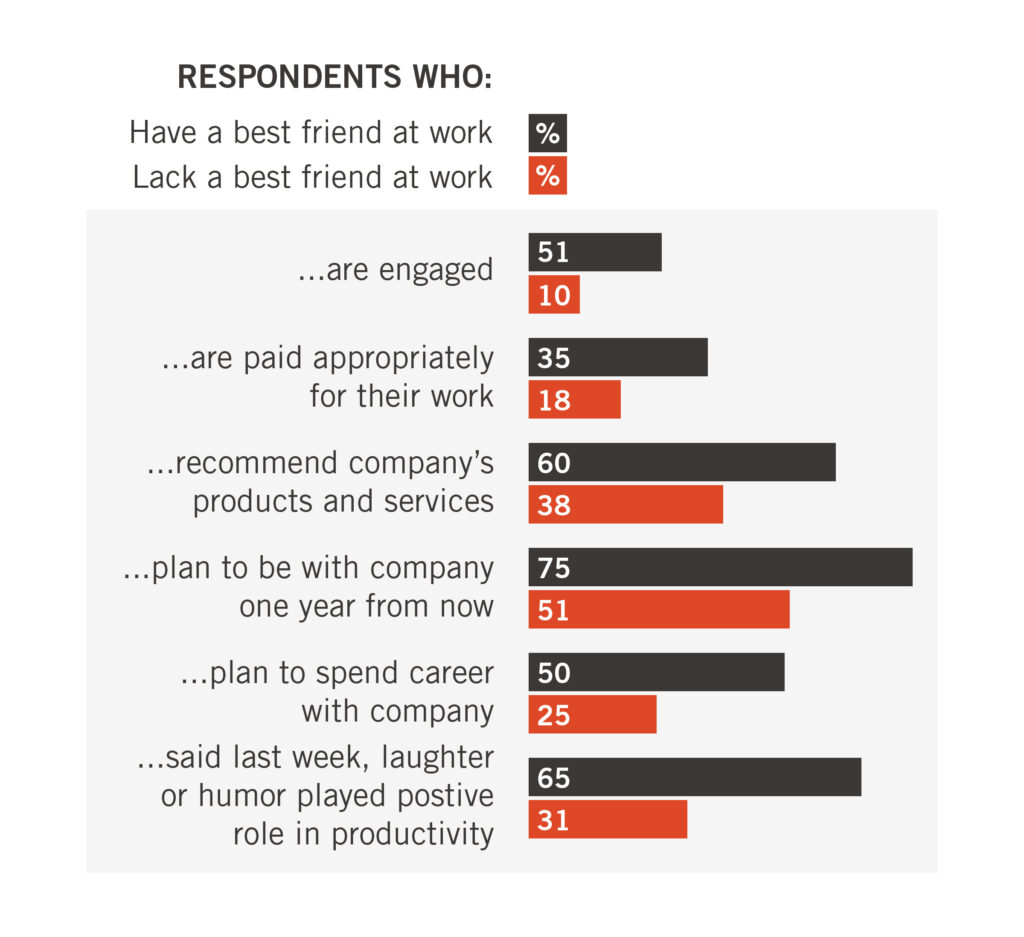

Fiscal and personnel metrics have long tied corporate success to employee experience (IBM 2018; Emmett, Komm, Mortiz & Schultz, 2021). Furthermore, Gallup’s recent research “Would Employees Thrive in a Four-Day Workweek?” concludes that the quality of the workplace will have a bigger impact on staff engagement, satisfaction and ultimately on productivity, than the number of days in the office or the hours in the week. “The quality of the work experience has 2.5 to 3 times the impact of the number of days or hours worked,” (Harter, 2021). The design and operation of the physical office has a new opportunity to contribute to the employee experience.

Historically, the workplace experience was measured by quantitative standards.

Employee experience (EX) evolution

Employee experience (EX) is a “company-wide initiative to help employees stay productive, healthy, engaged and on track,” (Bersin, 2021). EX is long lasting, “encapsulating what people encounter and observe over the course of their tenure at an organization,” (Lee, 2022). The employee experience evolution has been categorized into four phases, (Bersin, 2021):

- 1900: Industrial engineering focused on output. Fredric Taylor’s time-motion studies and the Myers-Briggs personality types, “all focused on trying to understand “what makes people perform better at work.”

- 1920-1980: Employee engagement concentrated on retention. The 1920’s Hawthorne studies documented that employees performed better when they felt they were being listened to. Thus, employee surveys were born. Gallup’s “friend at work” was a famous early predictor of employee retention.

- 2010-today: Feedback and response prioritized culture. Feedback trackers, such as NPS (Net Promoter Scores) and Glassdoor reviews offered avenues for improving the experience. Data from crowd sourcing, sentiment and mood analysis delivered near real-time feedback.

- Future: Integrated experience empowered individual productivity and well-being. Moving from a passive to active model, the employee journey will become a cross-disciplinary undertaking. Employees will demand customized, self-service, automated and curated experiences tailored to their work and life requirements.

Getting the employee experience right

Employee experience has increased in importance. Employees now have more choice and flexibility with an expanded workplace eco-system, that is, where work happens. Thus, the office experience has increased significance in the employee daily journey. The office is no longer the “only place in town” to get work done. The Bersin model explores the physical demands, psychological impacts, and environmental factors of employee experience in all the places work happens.

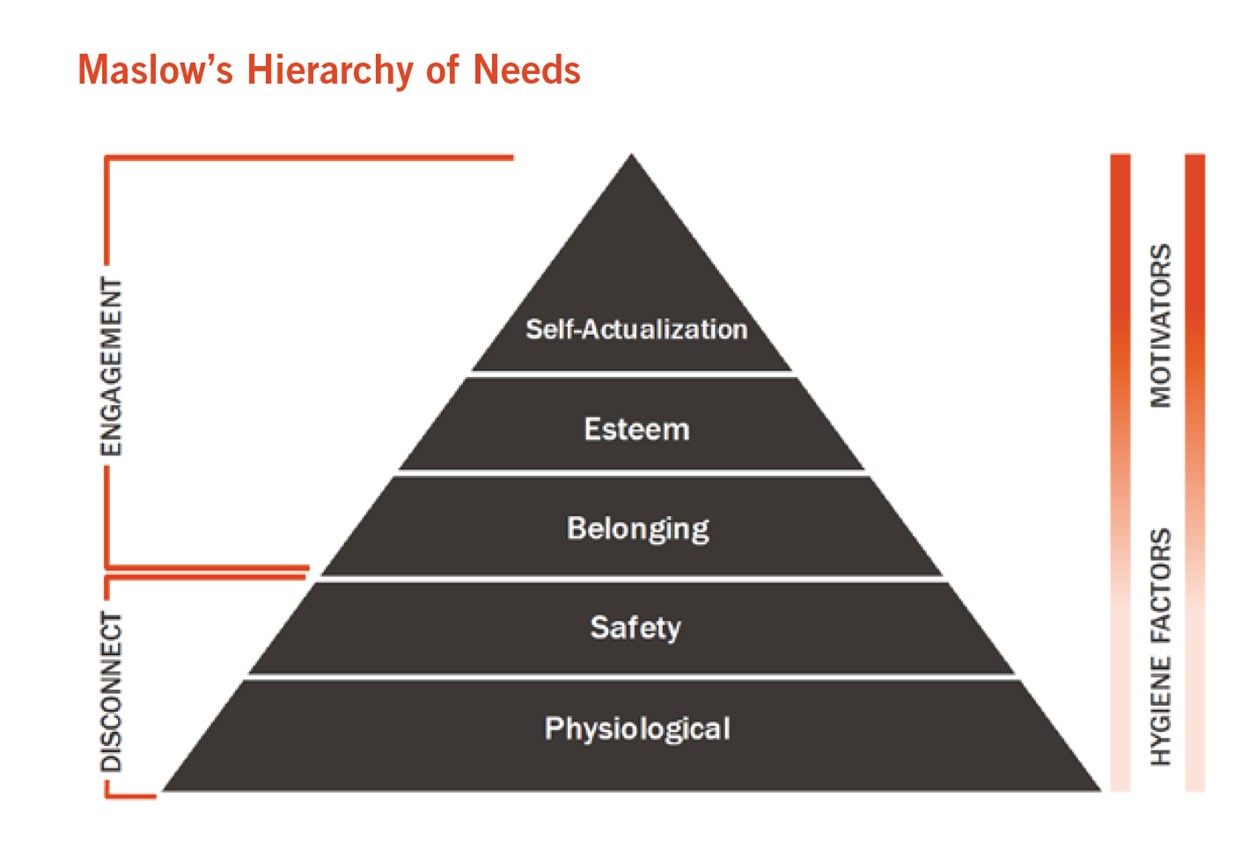

Discussion surrounding the physical demands of work evolved dramatically throughout industrialization from considering the weight a steel worker could lift in 1900, to ascertaining the real toll working extended hours has on the workforce. The bottom of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs pyramid calls out basic human requirements: physiological, “when (these) deficit needs have been ‘more or less’ satisfied it will go away and our activities become habitually directed towards meeting the next set of needs that we have yet to satisfy,” (McLeod, 2022). Innovative, creative, productive work in any setting cannot happen if the physical experience is hampered by physiological or safety needs. In other words, freezing temperatures or an aching back impacts the physical experience and impairs advancement to higher levels of knowledge work.

The Psychological impacts grounding employee experience can be viewed through the Self-Determination Theory lens. Four factors contribute to psychological satisfaction and influence work, (Martela & Tapani, 2018).

- Autonomy is the feeling of choice, enabled by flexibility in where, and in some cases when, the work gets done.

- Competence is having the spaces and tools to get the job done, in all the places work happens.

- Relatedness responds to the human need for connection. Teamwork, trust and equitable work circumstances support in person and virtual encounters.

- Beneficence is the strong connection to a shared purpose and meaning. Corporate values embedded into the culture influence the employee experience.

These psychological human needs impact the workplace and EX in a variety of ways. Taken together, these four factors are strong indicators of a positive workforce experience.

Environmental factors that influence workforce satisfaction and performance, and thus employee experience, are identified by Al Horr et al (2016), in Figure 3. These environmental factors play a significant role in positive EX.

Industries, companies and countries experiment with alternative workweeks

Table 1: Country-wide Experiments with the Four-Day Workweek (Brin, 2021, Haraldsson & Kellam, 2021; Joly, 2022)

In the last 20 years, in the U.S., alternative work schedules have become commonplace: nurses work three 12-hour shifts; some in the hospitality industry work four 12-hour days; others work flextime and split shifts. Or consider summer hours, where some employees would work four 10-hour days and get Fridays off. Recent press on the UK’s shortened workweek experiment also re-energized this issue internationally. Table 1 compiles recent country-wide experiments on alternative workweeks.

Why the work experience matters

Whether it is three days in the office and two at home or a four-day workweek entirely in the office, the place where work happens — matters. In a recent Leesman Index survey, 81% of participants found their home work environment enabled them to work productively, while the office environment scored 20% lower in enabling productive work (Roth, 2021). The comforts of working from home have raised the bar for the typical corporate office experience.

“If employers focused on improving the quality of the work experience, they could nearly triple the positive influence on employees’ lives compared to shortening the workweek,” (Harter & Pendell, 2021).

From the financial perspective, in the Financial Impact of Positive Employee Experience report, IBM’s Smarter Workforce Institute connected EX with retention, discretionary effort, and work performance, analyzing the relation between employee experience and an organization’s financial outcomes. Data from more than 45 countries and 22,000 employees indicated that the companies that scored in the “top 25% on employee experience, report nearly three times the return on assets, as compared to organizations in the bottom quartile,” (IBM 2018).

From the personnel perspective, employee journeys with an organization are marked by moments that matter, “those moments of togetherness…(that) actually improve outcomes,” (Chiarella, Marafante & Palter, 2022). McKinsey’s research “shows that people who report having a positive employee experience have 16 times the engagement level of employees with a negative experience and that they are eight times more likely to want to stay at a company,” (Emmett, et al 2021).

“The work environment must be a curated experience: unique, functional, and enjoyable.” (Foggie, 2022).

As there was a shift in sentiment for increased leisure time in the 1890’s, when the average workweek was 100 hours, there is now a shift in expectations about the experience of work. Defined by quantitative and qualitative measures, physical, psychological and environmental factors influence the employee experience. The office is not dead. In fact, it matters more than ever. The issue is not the days of work in a week or the days in the office, but rather the experience in the days.

References:

Al Horr, Y., Arif, M., Kaushik, A., Mazroei, A., Katafygiotou, M., & Elsarrag, E., (2016), “Occupant productivity and office indoor environment quality: A review of the literature,” Building and Environment, 105, 369-389.

Bersin, J., (2021), “The crusade for employee experience: How did we get here?”

Brin, D. W., (2021, May), “Countries experiment with four-day workweek.”

Chiarella, D., Marafante, F., Palter, R., (2022, May), “Workplace real estate in the Covid-19 era: From cost center to competitive advantage.”

Emmett J., Komm A., Moritz S., & Schultz, F., (2021), “This time it’s personal: Shaping the ‘new possible’ through employee experience.”

Foggie, L., (2022, July), “Coming back: Insights on the return to the office.”

Joly, J., (2022, April), “Four-day week: Which countries have embraced it and how’s it going so far?”

Haraldsson, G., Kellam J., (2021, June), “Going public: Iceland’s journey to a shorter working week.”

Harter, J., (2021, October), “Would employees thrive in a four-day work week?”

Harter, J., & Pendell R., (2021, September), “Is the 4 day workweek a good idea?”

IBM, (2018, June), “The Financial Impact of Positive Employee Experience.”

Lee, Sophia, (2022), “What is employee experience?”

Martela, F. & Riekki, T., (2018, July), “Autonomy, competence, relatedness and beneficence: A multicultural comparison of the four pathways to meaningful work.”

McLeod, S., (2022, April), “Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.”

Roth, P., (2021), “The wellbeing imperative.”