by Ian Aley, David Nelson, Alfonso Morales and Bill Elvey — Originally published in the July/August 2016 issue of FMJ — University facility managers handle a steady stream of used furniture, computers and specialized equipment. Rather than treating this material as waste, many institutions find creative ways to repurpose items, often through a surplus property department. This reuse process can help meet an institution’s environmental sustainability objectives while generating revenue to fund operations.

A university surplus department typically moves unwanted items to a central location for processing. Surplus employees wipe data from hard drives, clear capital equipment from internal tracking systems, and assess the functionality and value of items. Institutions and the general public may buy surplus items either through an online auction site or in-person sales floor. Some items are unsalable because they are broken, or because the market is saturated or non-existent. For instance, universities often receive more furniture than they can easily move through sales alone.

Beginning in the summer of 2015, the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW) formed a working group involving representatives from all the departments directly or indirectly involved in the handling of surplus materials at UW: waste and recycling, environmental health and safety, campus services (on-campus moving), space management office, purchasing, office of sustainability, building managers and surplus. This working group conducted a study of best practices of the surplus property departments of other large public research universities and a market assessment of external service providers.

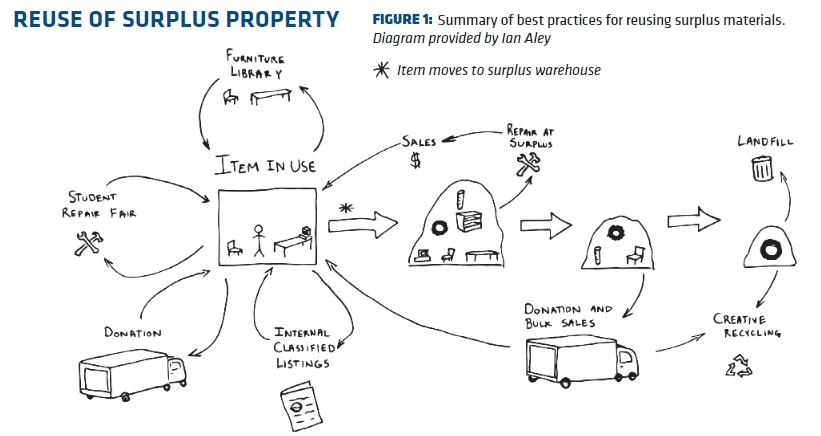

UW’s external market assessment found a limited number and scope of available external services providers. Because universities are largely on their own in handling surplus material, many have generated entrepreneurial solutions to achieve the objectives of revenue generation and waste diversion. Over the course of the study, UW encountered a number of creative strategies to divert unsalable material from the waste stream (see Figure 1 for a summary of these methods).

Facility managers translate the policies of their institutions into day-to-day systems. They negotiate organizational (financial, personnel, physical and technological) constraints to realize the sustainability mandates of their institutions. This article provides facility managers with practical tools and benchmark data that they can use to initiate or improve existing surplus property systems. While the focus here is on universities, FMs can adapt these lessons to various organizational contexts.

Strategies to reuse unsalable items

FURNITURE LIBRARIES

If the local market for furniture is saturated, furniture libraries can significantly reduce the amount of material going to landfills. These staffed or unstaffed warehouse spaces store furniture. In contrast to the large amount of space needed on a sales floor, furniture can be stored more efficiently in a high-density library format. Items are free to university and other public-sector employees as long as items are used at their place of employment.

Most states in the U.S. prohibit private individuals from bringing home publicly owned surplus material if the item does not first go through a competitive bidding process. Online or in-person sales satisfy that requirement. A furniture library distributing items for free does not qualify for this important method of repurposing material. Stanford University, Rutgers University, the University of Michigan and Oregon State University use the furniture library in tandem with a sales floor, reducing purchasing costs for campus departments and the amount of furniture going to landfills.

INTERNAL CLASSIFIED LISTINGS

The University of Oregon and Northwestern University run classified listings for university departments to post surplus items to sell or give away to other internal departments. These listings are similar to other online classified websites. They empower clients to repurpose items by connecting directly with one another, requiring little management from surplus staff.

Surplus material can be hazardous or contain sensitive data. Relying solely on internal classified listings could put the institution at higher risk for a data breach from improper disposition of surplus materials due to a rushed or uneducated decision by someone within a decentralized system. Facility managers can use internal classified listings to complement a centralized surplus operation and reduce the workload of surplus staff by finding new homes for items before they arrive at a surplus warehouse.

REPAIRS

Colorado State University stocks its surplus warehouse with necessary tools and parts to make small repairs, such as casters for rolling chairs. The University of Pittsburgh repaints filing cabinets to match a buyer’s desired color scheme if that means not sending it to a dumpster. Other institutions, such as Ohio University, expressed a desire to make small repairs but that they did not currently have the staff capacity to do so.

DONATIONS AND BULK SALES

The University of Minnesota, the University of Oregon, Oregon State University and other colleges donate items to non-profits, schools and other public agencies. The University of Oregon chose to discontinue relationships with certain charities after learning that donated items were sold for scrap metal.

The University of Michigan and UW have a hard time finding non-profit entities that want to receive donations of the type and volume of material handled by the university. Most surplus operations clear their warehouse floors periodically through bulk sell offs or auctions in which customers must take all furniture in the lot, including desired and undesired items. It is then the bulk customer’s responsibility to send undesired items to recycling or to the landfill.

CREATIVE RECYCLING

Multiple schools shred unsalable wood material and use it as mulch. Others shred or repurpose tires for use on playgrounds. The University of North Carolina breaks down unsalable wood furniture and sells the wood as lumber.

Operational best practices

TRIAGE

The earlier in the process surplus staff can assess an item and direct it toward its appropriate final disposition, the less transportation and staff time is required. An ineffective triage process may lead to delays or backtracking within the system after surplus material arrives at an inappropriate location.

The triage role requires communication with the surplus sales floor to stay up to date with supply and demand for certain items. For instance, if the surplus operation already has 40 high-quality filing cabinets in stock, it may choose to send lower-quality new arrivals directly to scrap metal for recycling. The triage role also requires specialized knowledge so employees can evaluate items for functionality and hazards.

The University of Washington developed a smartphone application (app) for surplus staff to triage items in the field. The app makes the university’s surplus material tracking system available to surplus staff at a loading dock or other remote location during a pick up. A product such as this could be shared or sold to other institutions, which could modify the app to suit their particular needs. An app could also include a section with an updated inventory of surplus items in stock, truck routing information, and a guide for identifying potential hazards.

SUSTAINABLE PURCHASING

Some universities work with suppliers in the purchasing phase to eliminate or streamline future disposal needs.

Oregon State University’s purchasing department negotiated with its supplier of office materials to ship all supplies in reusable totes rather than using cardboard and disposable plastics. They also requested that the supplier list reusable toner cartridges and recycled content paper first in their listings of items for purchase, hoping that the higher visibility would lead to more departments choosing these sustainable products. All Oregon State cafeterias offer reusable durable plastic clams called Eco2Go for takeout food, rather than more typical paper or Styrofoam containers. The purchasing director said she is planning to reduce the number of Oregon State’s modular furniture vendors and introduce durability and interchangeability requirements.

Temple University has introduced advanced user fees for all computer sales. This strategy embeds end-oflife costs in a product at the time of purchase, ensuring the user of the item pays for its eventual disposition. These charges are typically one to five percent of the sales price of an item. These fees, which only apply to the purchase of new items, can help incentivize the procurement of durable and/or used items. The revenue generated through these fees can fund waste, recycling and surplus operations.

Logistics, cooperation and staffing

Many surplus operations cross-report or co-locate with other departments. Surplus operations sharing warehouse space with waste and recycling or procurement departments make transfers particularly smooth. UW’s surplus operation shares a warehouse and trucking services with the materials distribution services (MDS). MDS trucks leave the warehouse to deliver items such as office paper and cleaning supplies. They load surplus items from the on-campus docks they already visit for deliveries and return with them to the shared warehouse space. UW saves on transportation, infrastructure and staff costs because of this cooperation.

The study found the number of staff required to run a university surplus operations ranged between one and 27 full-time equivalents with a mean of 10. Larger operations tend to employ many students in the process. Slim operations often serve a smaller client base, rely on another nearby university surplus operation or simply divert less waste from the landfill.

Training and communications

Oregon State University’s surplus department developed a series of videos to train student workers. These videos cover topics such as staffing the warehouse floor during public sales, picking up surplus items from loading docks and writing up posts for online sales. They help standardize procedures and contribute to ensuring safety and effectiveness.

Student workers often interface with the public and university departments, so the accuracy of communication can affect the reputation of the surplus operation. Many universities hire a new set of student workers each year or semester; instructional videos can reduce the staff time required to train new employees on policies and procedures.

Video can be a particularly effective method of educating both student and non-student employees; in many cases workers will prefer to watch a series of five-minute videos showing coworkers walking through practical situations to reading a manual. Surplus operations could also use videos to share information about the basic triage procedure with department administrators, building managers and other university staff to improve client knowledge of the surplus process.

These videos require very few resources to develop. Oregon State created a whole library of videos by hiring a single undergraduate student part-time for three months. The student used video equipment and software commonly available through university library systems. Oregon State suggested saving the raw video footage and video project in a format that allows for ongoing adjustment because policies and procedures change over the years.

Funding a surplus operation

Half of the university surplus operations that participated in the study funded their entire operation through sales.

It was rare for a surplus operation to run entirely through core funding. Some universities use a mixed model with core funds for administration, user fees for trucking and sales revenue for warehouse floor. Gross revenue generated by surplus operations ranged from US$190,000 to US$3 million in annual sales. Many universities split sales revenue with internal clients, especially for expensive items such as specialized equipment.

High on-campus land values can be a barrier to dedicating warehouse space to surplus material handling. UW dealt with this by establishing its warehouse in a lower-density area 10 miles southwest of the university. The University of Oregon, located 50 miles from Oregon State University, runs a slimmer operation by sending items to Oregon State’s more robust surplus operation. Northwestern University, situated just outside of Chicago, has no surplus warehouse, relying entirely on an internal classified listing for departments to sell or give away their items independently.

Takeaway message

Surplus property systems can capture significant value either by reducing the cost of purchasing new items or by generating sales revenue. Because of this potential, surplus property operations can run on a cost-neutral basis and can help institutions reduce their environmental footprint.

UW is now considering potential improvements to its surplus operation based on the processes, practices and innovations gleaned through this study of its peers. The strategies presented in this article can support facility managers in establishing or improving surplus property functions to achieve these financial and sustainability goals. – FMJ

Ian Aley is a Master of Science candidate in urban and regional planning at

Ian Aley is a Master of Science candidate in urban and regional planning at

UW-Madison focusing on community economic development and environmental

systems.

Bill Elvey is the associate vice chancellor for facilities planning and management at UW-Madison. He has 39 years of FM experience with 19 years in higher education. Elvey is a registered professional engineer, FMP and APPA Fellow.

Bill Elvey is the associate vice chancellor for facilities planning and management at UW-Madison. He has 39 years of FM experience with 19 years in higher education. Elvey is a registered professional engineer, FMP and APPA Fellow.

David Nelson is the director of purchasing at UW-Madison. He has more than 30 years of experience in engineering, quality and purchasing with organizations such as General Electric, Siemens and CUNA Mutual Group. Nelson has an MBA from DePaul University and is an ISM Certified Professional in supply management.

David Nelson is the director of purchasing at UW-Madison. He has more than 30 years of experience in engineering, quality and purchasing with organizations such as General Electric, Siemens and CUNA Mutual Group. Nelson has an MBA from DePaul University and is an ISM Certified Professional in supply management.

Alfonso Morales, Ph.D., is a professor of urban and regional planning at UWMadison. His work on urban marketplaces and environmental and social sustainability is nationally and internationally recognized.

Alfonso Morales, Ph.D., is a professor of urban and regional planning at UWMadison. His work on urban marketplaces and environmental and social sustainability is nationally and internationally recognized.