The pace of China’s industrial landscape evolution continues to gain momentum as more of the world’s economic activity begins its supply chain in the country. Gone are the days when a foreign firm breaking ground in Shanghai, Beijing or Guangzhou is an unusual sight.

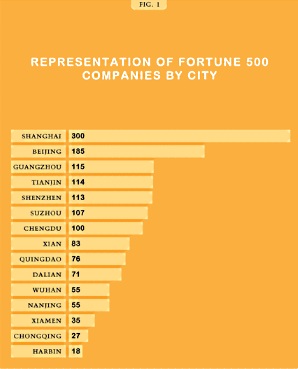

In 2006, 300 of the Fortune 500 companies had a representation in Shanghai, with Beijing and Guangzhou having 185 and 115, respectively.

For many, China is the location of choice, if not the location of necessity, in a business world that demands ever-increasing efficiencies and lower costs.

However, China is seeing cost pressures and inflationary constraints of its own. In response to rising cost pressures in China, firms are investing in Tiers II and III cities to try and establish a more cost-effective presence without overstretching their lengthening supply chains.

In return, these Tier II cities, many of which were not even on the radar of investors five years ago, are now becoming specialized in certain sectors and, as such, are preferred locations for particular groups of occupiers (see Figure 1).

This, in turn, has led to the clustering and development of critical mass where industry sectors gravitate to each other. Clustering in itself is a process that is as old as industrialization. As a firm moves to a new location, it trains a workforce and creates infrastructure that, in turn, can be leveraged by other occupiers.

In addition, supply lines are established which create economies of scale and ultimately savings for additional occupiers in the same sector.

This clustering is common with large manufactures such as in the auto or engineering sector. However, we are also seeing the development of research and development (R&D), technology, and BPO clusters in China.

These sectors are not reliant on hard infrastructure. They have moved into China’s hinterland to take advantage of a sea of under-utilized graduates and, in turn, created ad hoc teaching universities for some of the world’s leading industries (see Figure 2).

Which City to Pick and Why?

Locating a business to Tier II cities in a market like China is not an easy decision. It requires a number of inputs from all the stakeholders in the organization and the decision needs careful analysis before buy-in at all levels.

A range of different approaches have been used in selecting industrial locations in China. Some firms have traditionally relied upon the advice of their joint-venture partner, leading to the establishment of their business in locations that they have little knowledge of.

Other firms have been influenced by the location of competitors or companies in their particular industry. This trend has led to clusters of similar businesses in a particular area and the concentration of companies in larger cities where western media attention has been focused.

Whilst everyone knows about Shanghai and Beijing and has probably met people in their industry who have established facilities there, fewer industrialists in the United States or Europe know what cities such as Harbin, Chengdu or Wuhan have to offer.

Each firm is different and will have its own set of company-specific location criteria. However, our experience suggests that a relatively uniform and objective framework for assessing the optimal location for any particular plant or facility can be developed. We have worked with numerous multinational corporates to implement this business location decision process.

Regardless of company requirements, the overall objective remains consistent. It is to identify the best possible location for a business.

The numerous factors influencing a business location decision can be grouped together under five broad headings:

- Economy

- Labor

- Infrastructure

- Government/Business environment

- Real estate

Jones Lang LaSalle: City Selection Exercise

Jones Lang LaSalle has undertaken a city selection analysis in order to rank 30 individual factors with respect to 25 major cities across China.

Figure 3 shows how each city compares on the twin axis of cost and quality. With other things being equal, those cities above the line represent better value per dollar of cost. This suggests that Harbin, Chengdu, and Dalian represent good value for relatively low-cost activities; Qingdao and Tianjin are locations to consider for medium-cost activities; while Shanghai is the stand-out location among high-cost cities (see Map 1).

To reflect the requirements of different types of business, three scenarios were created to assess different cities for different users. These are as follows:

General Industrial—Equal weighting is assumed between each of the five major sets of criteria. This suggests a balanced approach between cost and quality factors.

Research and Development (R&D)—Firms seeking locations for R&D centers are likely to attach greater weight to the availability of high quality technical labor, as well as a supportive business environment, and will attach less weight to labor cost.

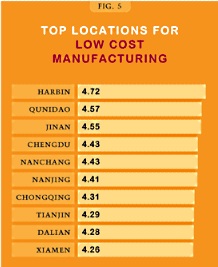

Low-cost Manufacturing—Locations for low-cost/high-volume industrial activities will be heavily influenced by cost factors, once a minimum standard of labor and infrastructure has been demonstrated.

General Industrial

This scenario reflects the existing dominance of the larger coastal cities, which score highest in terms of key parameters such as economic strength and dynamism, access to a large labor force, the quality of the business environment, and infrastructure.

Not surprisingly, the big three are closely followed by some of the hottest emerging cities such as Tianjin, Suzhou, Dalian, and Qingdao (Figure 4). Aspects of infrastructure that continue to trouble many firms operating in China include unreliable power supply and the lack of adequate logistics solutions in many locations. As China is divided into six major power grids, the cost and reliability of power supply can vary greatly from province to province.

For example, electricity prices on the average for cities in North-eastern China are at least 30% lower than that in the cities in Southern China. With the lack of a nationwide expressway system, roads and transportation options also differ greatly between cities. Surprisingly, a number of lesser-known cities such as Xian, Jinan, and Shenyang ranked relatively high in terms of infrastructure.

Research and Development

For R&D and other high-value/low-volume industrial activities, more importance is attached to the quality and availability of labor. Shanghai and Guangzhou again score in the top ten (Figure 5). While Beijing offers large number of graduates, the higher real estate costs in the city pushed it just outside of the top ten. Shenzhen does not score as well due to the limited number of local colleges and the low number of graduates. Shenzhen saw only 9,100 graduates complete their education in 2005 while most of the top ten cities for R&D see a minimum of 30,000 graduates pass through higher education annually.

Filling out the top ten list of location for R&D activities are a number of regional cultural and educational centers with well-established learning institutions. While availability of qualified workers is generally considered more important than labor costs for R&D and high-value/low-volume industrial activities, the ideal combination would clearly be those cities offering large number of graduates, along with lower labor costs.

On this basis, our analysis suggests that knowledge-based businesses locating to China without considering cities such as Nanjing, Wuhan, and Xian are missing potential access to a large number of quality university graduates who have lower salary expectations than their counterparts in major coastal cities. While Shanghai and Beijing are not bad choices for R&D centers, will Nanjing, Wuhan, Xian and a handful of other cities represent better alternatives?

Low-cost Manufacturing

Companies seeking locations for high-volume/low-value manufacturing activities will typically attach greater weight to cost factors. This elevates the rankings of a number of lesser-known Tier II cities such as Harbin, Jinan, and Nanchang.

As expected, none of the Tier I cities made it into the top ten best locations under this scenario. In fact, Beijing ranked lowest (most expensive) of all the 25 cities. Tax incentives are an important consideration for the location of low-cost manufacturing facilities in China. In considering this factor, we need to take into account both the level of tax incentives and the local government’s ability to deliver them. Tax incentives are predetermined (based on the level of sponsorship of an industrial zone) but local governments often promise additional tax rebates or special subsidies to make their zones more competitive. As each local government differs in their financial strength, they also vary significantly in their ability to sustain their promises in the long run.

When we combined tax incentives, government responsiveness, and financial strength all together, our results highlighted an interesting set of cities including Xiamen and Dalian as potentially attractive locations.

As land prices climb rapidly in Tier I locations such as Shanghai and Beijing, the cost of real estate is also becoming a major concern. There is a clear relationship between the maturity of cities and cost of real estate, with the cost of both industrial land and rents for industrial premises in Shanghai and Beijing, being more than four times those in lesser-known cities.

The cheapest locations from an industrial real estate perspective include Nanchang and Jinan, where relatively few western multinationals are currently located. Thus, we advise firms to look at these cities if they wish to reduce cost and get ahead of their competition.

Looking Ahead

Given the long-term nature of industrial investments, more opportunities can undoubtedly be discovered (and risks avoided) if we consider the ways in which China’s industrial landscape is likely to change in the years ahead.

Whether you are ready to invest in two months or two years’ time, predicting the changes ahead for a potential investment location will assist in ensuring a more successful business outcome.

For this reason, our analysis of competing locations is a good starting point for understanding the various cities’ current strengths and weaknesses.

However, it is crucial for clients to examine locations not just as they are today. It is also vital for them to ask the following forward-looking questions when considering industrial investment decisions in China:

- Which cities will become the next investment hot spots?

- Will the continued concentration of activity in major cities result in worsening labor shortages, thereby increasing costs and reducing the attraction of these cities relative to new and emerging locations?

- How will changing land policies and potential land shortages in some locations affect expansion options?

- Will major infrastructure projects bring forward new areas of opportunity?

- Which governments are promoting incentives to your industrial sector and what is their capacity to deliver on these incentives?

About the Authors

Justin Kean is an Associate Director at Jones Lang LaSalle.

Trent Iliffe is Regional Director, head of Industrial China. He is responsible for the day to day running of the Industrial business with a focus on growing this division across all aspects of Industrial property.