by Stephen Kleva — A critical component of facility management is the ongoing maintenance and regular inspection of equipment, infrastructure and systems within facilities. Accidents and failures within the nations hundreds of thousands of facilities and plants do not typically receive the same level of national attention as major infrastructure or equipment failures in the public space (bridges, cranes, etc.), yet they happen every day. It is the responsibility of the facility manager, and, ultimately, the facility owner, to ensure safety and protect investments in facility assets. The consequences and costs of accidents over the years have driven the evolution of state and municipal laws shaping the “safety inspection industry” that we know today. A patchwork of jurisdictional and commercial responses (laws, codes, ordinances) has evolved as political and legislative responses to these accidents. In some cases, industry associations have assumed responsibility for codifying recommendations and best practices around equipment and infrastructure maintenance/ inspection.

The cumulative effect of a greater national concern with citizen and worker safety is a trend toward stricter inspection laws and greater penalties for noncompliance. Inspection Laws Getting Stricter New York City, the largest and one of the nations oldest cities, is leading the way in legislating stricter safety inspection laws in many areas. It has recently made two key inspection laws for boilers and elevators much stricter.

|

|

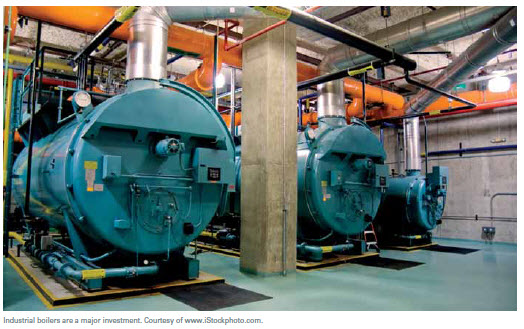

Boilers. Boiler inspection is legislated either by the state, municipality or city. Municipal laws govern safety inspection in the five boroughs of NYC. Most of the citys 800,000+ buildings are heated with lowpressure boilers, and every year a variety of boiler-related accidents occur that interrupt service to facilities, building occupants and businesses. Some result in significant damage to the building and its equipment, and in some cases, even loss of life. Effective July 1, 2008, the city changed its boiler inspection laws. The new law requires that if boiler defects are found during a jurisdictional inspection, the boiler owner must have the defect(s) repaired by a licensed boiler repair contractor, and the boiler must then be re-inspected by an approved inspector to confirm the defect has been repaired. Once the re-inspection is complete, the boiler owner has 45 days to submit to the city an Affirmation of Correction (BO-13) that has been signed by the approved inspector attesting to the compliance of the boiler. Penalties for failing to comply with these new requirements can include fines of up to $1,000 per boiler per year. Until this law was changed, there was essentially no penalty for noncompliance if deficiencies/problems were detected. Property owners were penalized for not having the boiler inspected, yet if defects were found, there were no standardized penalties for non-compliance in fixing those defects.

Elevators. A new elevator inspection law went into effect in New York City in January 2009 that affects inspection of NYCs 63,000- plus elevators, escalators and related equipment. The new law stipulates that all vertical transportation equipment must be inspected by a licensed private third-party inspection agency or, if performed by an elevator maintenance company, there must be a third-party witness present who is not affiliated in any way with the maintenance company due to potential conflict of interest issues. In short, there must be a witness two parties present at any elevator inspection. This law was specifically designed to remedy conflicts of interest inherent in the existing law, which in too many cases, apparently, led to less-than-adequate inspections and repairs, jeopardizing public safety. The law also requires that any defects found be corrected within 45 days.

Building Facades. Many U.S. cities have formal faade ordinances or municipal laws that require periodic inspection of building facades designed to help inspectors identify unsafe conditions such as faade components or materials that are loose or unstable and at risk of causing serious injury or damaging property. Some cities have very stringent requirements for these inspections (for example, requiring hands-on inspection of all facades by licensed architects or engineers), while others require only visual street-facing inspections, and still others do not have regulations regarding facade inspections at all.

In 2005, ASTM International, the international standards organization that develops and publishes voluntary technical standards for a wide range of materials and services, developed and passed a set of updated recommendations regarding faade inspections known as ASTM E2270-05 Standard Practice for Periodic Inspection of Building Facades for Unsafe Conditions. The new standard provides cities with a comprehensive benchmark that draws on the best existing facade ordinances in cities across the U.S. The recommendations outline the requirements and procedures for conducting facade inspections. The standard was designed to help cities that do not have a facade ordinance adopt one and assist cities with existing ordinances to revise them to reflect best practices. The standard is intended for adoption by model building codes, local municipalities or building owners. The ASTM subcommittee that developed the standard based it on review of many existing facade ordinances and the experience of subcommittee members, which included representatives of leading US architectural and engineering firms, industry associations material manufacturers, contractors and others. The cumulative effect of the greater national focus on safety and inspection is a trend toward stricter inspection laws and greater penalties for noncompliance.

Balancing Proactive and Preventive Maintenance

|

|

While facility owners carry the risks and liabilities associated with a variety of equipment and infrastructure, facility managers are tasked with the day-to-day responsibility of repairing equipment and ensuring regular facility and equipment maintenance and inspection all as cost effectively as possible. Between the mandated inspection of facility equipment and systems and routine maintenance activities (preventive maintenance), lies a murky, less-defined area of proactive inspection, maintenance and risk management for the facility manager. The better the facility manager is at balancing the two, the smoother and more predictable are day-to-day operations. Yet balancing financial and operational efficiencies with safety, productivity and legal requirements is a complex task. On top of this, the roles and responsibilities of the facility manager are expanding due to greater corporate focus on cost restraint and operational efficiency, coupled with government regulations. Depending on the size and type of facility, responsibilities may include security activities, engineering and architectural services, ensuring facility compliance with relevant codes and regulatory requirements (hazardous material handling and disposal, and other workplace safety issues), management of computer and telecommunications systems, and buying, selling or leasing real estate.

To maximize overall operating budget and reduce costs, there is always the temptation to defer maintenance. While this may provide short-term gains, it will cost the organization long-term. Performance will suffer, reliability will be significantly reduced, and the organization may find that it is no longer in compliance with regulatory requirements and is subject to monetary fines. Many facility managers have learned through experience that proactive maintenance of equipment and systems saves money in the long run, reduces disruptions to tenants, and enables a more predictable stream of financial outlays and maintenance costs. When performed strategically and efficiently, preventive maintenance is less expensive than reactive, “breakdown” maintenance.

|

|

A strategic maintenance plan is one of the most effective tools available to facility managers. With such a plan, there is budget available to proactively deal with facility needs rather than reacting to problems after they occur, which makes maintenance a costly, ad-hoc process. A strategic and effective maintenance plan is also an essential part of a risk management strategy, since it enables potential hazards to be identified at an early stage, and preventive action to be taken accordingly. The bottom line is that maintenance costs money. Ad-hoc, incident-driven maintenance is only less expensive in the short term, and it is certainly less predictable. The hidden costs of this approach may not become apparent until later on.

Safety Inspection Challenges for Facility Managers

In almost two decades working in New York City, we have found that it is not uncommon for facility managers not to know which equipment inspections are mandated, how frequently they must be performed or when they are due. This is one of the reasons NYC boiler inspection laws recently got stricter. Why and how is this the case? We have found several common causes: 1) the laws pertaining to facilities and equipment can be very cumbersome, if not overwhelming; 2) fully understanding or interpreting the laws can be difficult; 3) poor communication of new regulations by agencies; 4) job turnover amongst facility managers; and 5) lack of historical facility data. Combined, the factors can make it very challenging for information and regulations to reach the right person at the right time.

Technology Can Aid Facility Maintenance and Management

|

|

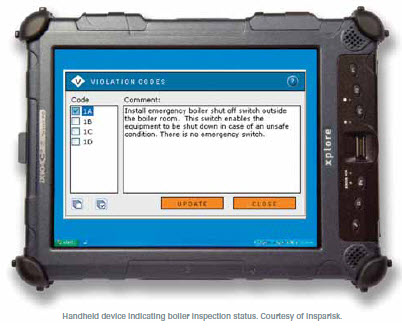

Technology came relatively late to the field of facility management, but it has become a very useful tool for even small to mid-sized facilities. Although technology is no panacea, it does help to manage many of the tasks and responsibilities associated with safety and maintenance activities. A wide variety of applications and functionalities are available today (at many price points) to meet almost any facility management need: inspection, project, equipment, information technology and telecommunications, and maintenance and service.

Customary functionality of applications enables facility managers to better manage and verify their maintenance activities documents. Insurance companies, property owners and real estate managers benefit from this comprehensive electronic record of safety inspection and maintenance activities. In conclusion, it is important for facility managers to stay current with their municipality or state laws, and wherever possible, implement processes and technology to better manage the responsibilities associated with their jobs and facilities.

Stephen Kleva is president and CEO of Insparisk,

a national safety inspection company. Insparisk

manages safety inspection for boilers, elevators,

fire detection/suppression systems, facility

facades, HVAC equipment, and electrical panels. Its

subsidiary City Spec, Inc., performs inspections on

low-pressure boilers within the city of New York.

For more information, visit www.insparisk.com