March 2018

It certainly isn’t a new idea; that what is good for the planet is also good for our wallet. Whether on the small scale of one’s home or on the large scale of our cities, it seems that planners and facility managers are becoming increasingly aware of opportunities to save money by preserving natural resources. In a world where every 10 years, an area the size of Britain disappears under urban development,[1] and the increasing percentage of humans that so choose to inhabit cities, it is natural to consider the impact that humans are having on the plants and animals that our buildings displace. What is the role of native species in our built environment, how do current tools and rating systems such as LEED aim to incorporate native species, and how can we work with them to save money when managing our facilities?

As the Green Building Alliance aptly summarizes, non-native and exotic species of plants, which have been introduced directly or indirectly by humans, often require extensive care in the form of water, fertilizer, pesticides, and other maintenance. Invasive plants are typically non-native species that grow and spread aggressively to the point of displacing other plants. Some are hard to control and may even dominate whole areas, disrupting ecosystems and diminishing biodiversity. Native plants, on the other hand, are an integral part of local ecosystems and flourish in their specific conditions without soil modifications, chemicals, or excessive water. Finally, adapted plants are non-native, but thrive under a certain region’s temperature, soil, and rainfall conditions without becoming invasive.[2]

Maidenhair Fern is a native species on Leonardo Academy’s Valley Ridge Preserve in Richland County, WI.

Native vegetation includes all the plant species that occur naturally in a geographic region and provide essential habitat for native insects and animals. These plants have evolved together over time to form ecosystems that are well-suited to the particular combination of soil, temperature, nutrients, and rainfall of their region. As a result, native species are naturally resilient because they are adapted to local conditions.

When it comes to managing the grounds of a building, whether it be lawn, decorative foliage, or garden beds, money and resources are often wasted trying to cater to the needs of plant species not equipped to survive under the climatic conditions it is in or combatting the destructive effects of invasive species.

Plants evolved to thrive in a specific geographic region are uniquely equipped to live without the need for human support. They survive based on the amount of light, water, and soil nutrients available to them naturally. As such, the cost of maintaining native and adapted plant species on a building site is much lower than it is to tend to plants that aren’t naturally suited to survive in their given environment. What’s more, native plants are typically no more expensive than non-native plants to purchase and plant in the first place.2

For building sites specifically, the cost saving opportunities associated with using native plant species extend beyond the reduced need for inputs, such as water, fertilizer, and labor. Native plants additionally support the architecture of the site’s soil and help to prevent erosion and absorb storm water runoff. In this way, native vegetation a passive form of preventative maintenance.

As urban spaces become increasingly dense however, the availability of surrounding site area to incorporate any kind of vegetation is being diminished. Green roofs and cool roofs can save energy, reduce neighborhood temperatures, and protect human health. They have a strong regulating effect on the temperature of underlying roof surfaces and building interiors, reducing the energy needed for building cooling and the effects of the urban heat island effect. [3]

In addition to awarding points for onsite native vegetation and green roofs, the LEED rating system awards points for protecting native vegetation and habitat outside of the project boundary. Project teams can offer their financial support by means of offsite native vegetation credits to preservation and conservation organizations as well.

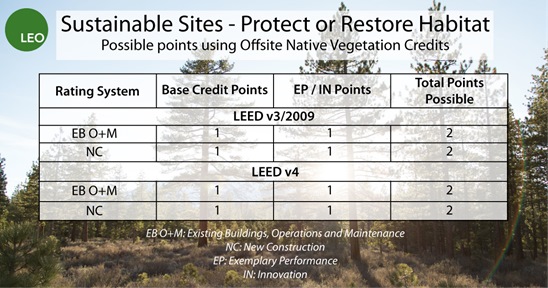

It is important to note that the evolution of the LEED rating systems from version 3 to version 4 bring with it some evolution of these credits as well. As illustrated below, each building project can earn up to 2 points for offsite native vegetation. However, while v3 allows project teams to purchase offsite native vegetation credits anywhere in the world, LEED v4 requires that the area supported by the project team is within reasonable geographic scope. Specifically, under v4 financial support must be provided annually to a nationally or locally recognized land trust or conservation organization within the same EPA Level III ecoregion, in the same state of the project, or within 100 miles of the project for projects outside the U.S.

The above table breaks down the LEED points that can be earned using offsite native vegetation. Note that in the above figure, the likelihood of LEED NC projects earning points for offsite native vegetation is very small, as new construction projects have been unable to register under v3 since October 2016.

Numerous building managers have found that offsite native vegetation is a relatively low-cost option for earning LEED points. According to Michael Arny, Leonardo Academy President and Director of Sustainable Building Services, “If LEED project teams wants to bump up their score, this is a very straightforward way to do that. Offsite native vegetation credits can help with both continuous improvement and hitting specific certification levels goals. Many find that purchasing credits to protect native vegetation offsite is a less expensive options than pursuing other credits.”

Whether supporting native plant species within your buildings site, on your roof, or on an offsite land trust or conservation, for LEED certification or general sustainable building management, building owners and managers can reduce their operating and certification costs by supporting native plant species and local biodiversity.

[1] Planet Earth II (2016) s01e06 Episode Script | SS. (n.d.). Retrieved March 16, 2018, from https://www.springfieldspringfield.co.uk/view_episode_scripts.php?tv-show=planet-earth-ii-2016&episode=s01e06

[2] Native Plants. (n.d.). Retrieved March 16, 2018, from https://www.go-gba.org/resources/green-building-methods/native-plants/

[3] Garrison, N., & Horowitz, C. (n.d.). Looking Up: How Green Roofs and Cool Roofs Can Reduce Energy Use, Address Climate Change, and Protect Water Resources in Southern California(p. 2, Rep.). Natural Resources Defense Council. <https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/GreenRoofsReport.pdf>