This article originally appeared in the September/October 2022 issue of FMJ

by Erik Jaspers, Nathalie Perrier and David Stillebroer — Previously known as sustainability and often denoted as the triple bottom line of people, planet and profit, ESG is the acronym for environment, social and governance. Whereas CSR (corporate social responsibility) is about an organization’s sustainability agenda, ESG is about measurable actions and outcomes.

One could state that the concept is far from new, but clearly it has gained significant momentum over time. ESG is no longer profiled as a corporate issue; it has entered the realm of politics and policy making. In the U.S., the state of California published the California Environment Reporting System (CERS) in November 2020. The EU is preparing its Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) next to the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD).

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) plays a central role in this. In the context of IPCC, hundreds of leading scientists, technologists and other experts from 195 member states work together to identify aspects and root causes of climate change and describe consequences. In 2022, IPCC published its sixth assessment report.

Tangible ESG approaches for the real estate and facility management industries are still in their infant stages. So, what is looming ahead? What can FMs expect in terms of ESG influences?

ESG and sustainability

ESG and sustainability both address environmental and social aspects; the main difference is that ESG is defining specific compliance rulings. Transitioning from sustainability practices to ESG is expected to drive the evolution of voluntary business approaches to formal performance management, measurement and disclosure.

Environment

This dimension focuses on balancing human activity with its influence on the environment. Research has made clear that the emission of greenhouse gasses (GHGs) is the most dominant reason.

The environmental aspect of ESG is much about reducing carbon and other GHG emissions. In this domain, additional regulations and reporting standards are expected to enter the market within the next two years. It is here where the biggest problem has been identified and hence the most attention is given.

Regulations are being developed by multiple governmental, standards and financial bodies. Businesses and organizations themselves are developing policies on corporate level.

The real estate and FM industries are tangibly linked to the environmental ESG aspects such as use of energy, water and materials. Approximately 40 percent of CO₂ emissions stem from buildings. GHG regulations will require action from real estate and facility managers. Next to any desire to improve the eco-footprint of buildings, there will be an obligation to adhere to regulations. ESG is at least partly becoming a case of compliance in the years to come.

Social

Social criteria are about addressing societal problems around poverty, inequality and mental health. It profiles important principles like diversity, equity and inclusion (DE&I). GRESB describes the social dimension as building trust and societal engagement. In its essence, the social dimension of ESG tends to be less firmly defined than the environmental dimension.

But specifically in this dimension, the real estate and FM professions have a unique and concrete role to play. In terms of services and products acquired, fair trade principles are fully in line with ESG objectives. FMs are the provisioners of the working environment. User health and safety, engagement, workplace experience and well-being are pivotal elements in the workplace conversation. Standards such as WELL have user well-being at their core.

Notably, the workplace paradigm is undergoing a fundamental shift toward explicit hybrid models. This development was accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic’s environmental influence. FMs have managed the pandemic’s impact on the strong relationship between the environmental and social dimensions of this industry.

Governance

This dimension addresses the system of practices, processes and procedures used in the operations of an organization. It is set up to govern organizations and foster compliance to regulations and law. Formal reporting resides in this dimension, aimed at disclosing information to the relevant stakeholders.

Governance is typically a concern of senior management. However, there are tangible contributions for real estate and facility managers to provide: well-structured environmental and social information for corporate level ESG reporting on the aspects of buildings as operated, workplaces and their use as well as FM services rendered.

ESG: Imperative for any organization

In the context of corporate sustainability, organizations have adopted sustainable practices over the past years, but as ESG is taking shape, they will face additional pressure from their stakeholders and regulatory and governmental bodies.

- As investors want to invest in more resilient businesses, organizations that have effective ESG risk management in place will be more attractive to them. Note that the ESG reporting initiative of the SEC clearly indicates the relation between the stock value of companies and their ESG-related policies and achievements. For real estate operations, this implies that the value of buildings will increasingly relate to their risk profile regarding the environment. Asset valuation in view of ESG is the domain on which the TCFD is concentrating, its membership being made up of financial institutions.

- As governments need to achieve their net zero targets, 192 countries have defined their national determined contributions. To reach their objectives, they must deploy directives and legislations to drive the change in both the public and private sector.

- More than ever, employees desire purposeful work; thus, organizations that are taking a proactive ESG approach become more attractive. Organizations that have a positive impact on the planet and society might experience increased interest of talent and see lower levels of attrition.

- Customers want and need to buy products/services from companies that demonstrably care for the environment and society. Research shows that consumers are willing to pay up to 5 percent more for environmentally friendly products.

Eco-accounting

The relevance of compliance firmly came on the radar in the real estate and FM industries when lease accounting standards were extended. As properties are leased, a dominant part of the building portfolio was subject to new financial reporting standards for which well-structured, correct and traceable data on the building leases had to be provided.

The same type of approach is now ongoing around what can be denoted as eco-accounting. Development of these accounting standards is in progress. The expectation is that they will show similarities with the financial accounting principles. The key currency of eco-accounting will be CO₂E. The fundamental objective of eco-accounting will be the formal disclosure of the organizational footprint in terms of CO₂ emission and the embodied CO₂, the CO₂ ”in stock,” so to say. Compare it to capital expenditures during the year next to capital allocated to assets on the balance sheet.

Under ESG, there are three scopes of emission defined:

- Scope 1: Direct GHG emissions that occur from sources that are controlled or owned by an organization.

- Scope 2: Indirect GHG emissions associated with the purchase of electricity, steam, heat or cooling.

- Scope 3: Emissions that are the result of activities from assets not owned or controlled by the reporting organization, but that the organization indirectly impacts its value chain.

Assets consequently will obtain two currencies: the financial currency to acquire and operate them next to the GHG currency on ownership and use. And this will provide for a new perception of asset value itself.

Asset depreciation and retirement

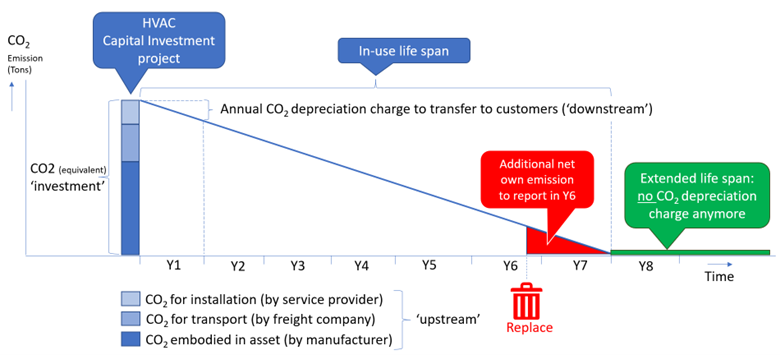

If an organization acquires a new HVAC, the equipment must be manufactured, and CO₂ emissions related to its manufacturing will be charged by the manufacturer and recorded as embodied in the asset itself. The equipment will have to be transported to the building site, which incurs CO₂ emissions that are charged by the transportation company. Also installing the system incurs CO₂ emissions, charged by the service provider doing the installation.

These types of emission factors are upstream emissions: emissions incurred by doing business with one’s suppliers.

Figure 1: Asset depreciation and retirement in view of eco-accounting. Image courtesy of FMJ. Click to enlarge.

In this example, the HVAC system should operate for seven years. During these years, the CO₂ investment can be depreciated (assumed linear), and that depreciation volume is charged to the organization’s customers as part of the downstream emissions. Downstream emissions are the ones that an organization charges to its clients over products and services rendered.

What if there were two potential retirements: one earlier than projected, one later than projected? If the organization retires the asset sooner, the volume of CO₂ not yet depreciated will have to be reported as net emissions. This could come as an additional cost as governments are taxing CO₂ emissions or are planning to do so.

When the asset is in use for a longer time, the situation changes: after seven years, the CO₂ investment is fully depreciated, and the clients are no longer charged for it. The goods and services effectively become less expensive for the organization’s clients.

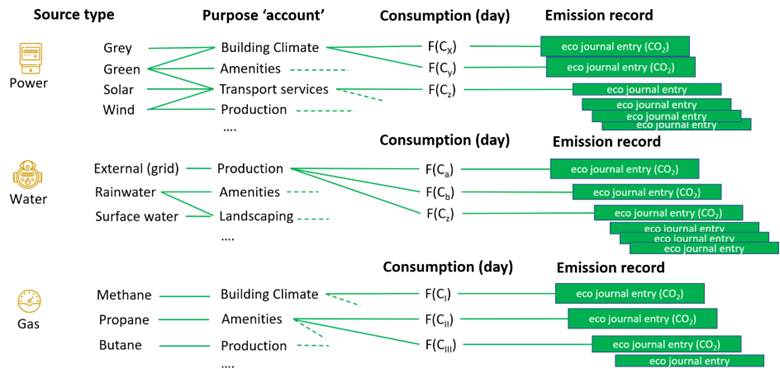

Tracking net own emissions — eco-journal entries

As the HVAC in this example is running every day, it will consume energy that will be responsible for direct CO₂ emissions. Buildings contain energy-consuming assets and eco-accounting and ESG reporting requirements around buildings and workplaces will demand for a firm ledger-type of recording.

Different sources of energy have different levels of CO₂ emission per kWh associated to them. Solar power will have a very small CO₂ footprint per kWh in comparison to grey power (created from gas, coal or oil). In terms of eco-accounting, consumptions for specific purposes that must be reported on must be classified (indoor climate, amenities, internal transport like elevators and escalators, production, etc.).

The actual consumption level from a source for a specific purpose is calculated into a record of effective emission. The eco-journal functions as a basis for disclosure.

The records show the explicit relationship between the use of natural resources and the footprint of the various building functions. Energy sources that carry a high level of CO₂ emissions per kWh will now receive another type of cost associated with them: the emission level. Again, when these emissions are taxed, this might fundamentally change the view on what resource would be most attractive to use.

Defining RE & FM ESG policies

This all may seem elaborate, but keep in mind that the approach on eco-accounting represents a normal operating procedure in the world of finance. In other words: doable, but a real project.

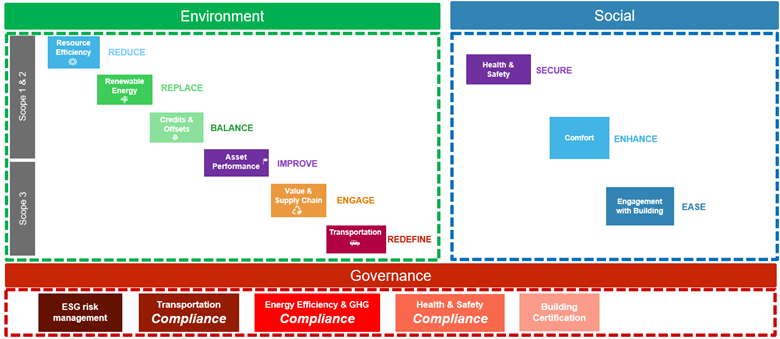

The three dimensions (environment, social, governance) each set forward a set of requirements, objectives or options that will require careful prioritization.

Figure 3: ESG aspects for real estate and facility management. Image courtesy of FMJ. Click to enlarge.

On the environment dimension, the main topics are:

- Resource efficiency: Reduce the energy used by rationalizing the building portfolio and conducting operations more efficiently for energy and water.

- Renewable energy: Replace carbon-intensive energy with low-carbon sources through on-site production or purchase.

- Credit & offsets: On the journey to net zero buildings, start with neutral buildings; and to the level that this is not possible, offset the remaining emissions.

- Asset performance: Extend the life cycle of assets and focus on delivering their maximum efficiency performance.

- Value & supply chain: Engage with the suppliers around consumables, material and equipment as in-use. Stimulate suppliers to reduce the impact of these goods/services but also improve own waste management (recycling).

- Transportation: Redefine the transportation options around buildings to allow greener commuting modes (installing EV chargers on site as an example) and minimize commuting distances.

On the social dimension, the main topics are:

- Health & safety: Secure the safety of all people on site, improve air quality, have proper cleaning, ensure distancing when called for and enable optimal layout.

- Comfort: Enhance the comfort, optimizing temperature, humidity, acoustic, lighting.

- Engagement with the building: Ease the interactions of the building users with the building and workplace services to deliver its full capabilities with a frictionless experience.

The governance at building level is about ESG risk management, compliance in reporting, certification and disclosure.

In the end

In setting up an ESG agenda for real estate and FM departments and organizations, the following approach could work well:

- Connect with corporate ESG management to identify corporate priorities and policies. This way, the RE & FM functions can align their own priorities.

- Create a backlog of topics, organized by priority — the most important topics first.

- Start with profiling (quantification) of the building/workplace portfolio: know what the actual performance is to identify where to invest first.

- Take an iterative approach to the project: learn from experiences as the project moves on and adjust approaches over time based on what works well and what does not.

Real estate and facility managers will have a lot on their plates with ESG for the coming decades. There are excellent reasons to be proactive.

Erik Jaspers, IFMA Fellow built his over 40-year career in IT, starting in production automation with Philips Electronics. For the last 23 years, he has been working for Planon Software. He has held senior management positions in developing Planon’s software solutions, currently working on Planon’s prodeuct strategy and innovation policies. He is a member of the IFMA EMEA Board and member of the (German) GEFMA Digitization workgroup.

Erik Jaspers, IFMA Fellow built his over 40-year career in IT, starting in production automation with Philips Electronics. For the last 23 years, he has been working for Planon Software. He has held senior management positions in developing Planon’s software solutions, currently working on Planon’s prodeuct strategy and innovation policies. He is a member of the IFMA EMEA Board and member of the (German) GEFMA Digitization workgroup.

Nathalie Perrier has gained experience in software development, software product management, marketing and product strategy for more than 20 years. She has been working for a variety of technology companies and IT service companies. The last 15 years, she has worked in various leadership roles for Schneider Electric, specializing in building software from design to build and up to operation and maintenance. With the urgency of climate change, Perrier decided to focus on sustainability. She is leading the development of the joint proposition for smart sustainable buildings with Planon Software while helping Planon reshape their ESG strategy and commitments as a company.

Nathalie Perrier has gained experience in software development, software product management, marketing and product strategy for more than 20 years. She has been working for a variety of technology companies and IT service companies. The last 15 years, she has worked in various leadership roles for Schneider Electric, specializing in building software from design to build and up to operation and maintenance. With the urgency of climate change, Perrier decided to focus on sustainability. She is leading the development of the joint proposition for smart sustainable buildings with Planon Software while helping Planon reshape their ESG strategy and commitments as a company.

David Stillebroer has more than 20 years’ experience in facility management, real estate and IT and is responsible for solution strategy at Planon. He has a background in hard services and soft services and has been real estate portfolio manager, software implementer and product manager. Stillebroer has also been part-time lecturer in real estate management at Rotterdam University.

David Stillebroer has more than 20 years’ experience in facility management, real estate and IT and is responsible for solution strategy at Planon. He has a background in hard services and soft services and has been real estate portfolio manager, software implementer and product manager. Stillebroer has also been part-time lecturer in real estate management at Rotterdam University.