By Peter S. Kimmel, AIA, IFMA Fellow

Publisher, FMLink

In March 2008, Napa Valley wine producer Far Niente went live with its FloatovoltaicTM solar array, the first-ever system and technology of its kind in the solar industry. Many vineyards in Northern California have been going solar. As vineyard buildings are not large enough to house all the solar cells necessary, many vineyards have had to usurp valuable land for the solar arrays, thereby losing some of their crops.

|

|

| Aerial view of Far Niente. |

But Far Niente, which romantically translated means “without a care,” didn’t want to sacrifice so much of its land (and its grapes). So management, which was totally committed to using solar energy to provide all of its electricity needs, looked into the idea of securing solar panels on “floating” pontoons on the vineyard’s irrigation pond.

The final solution involved securing nearly 1,000 solar panels on pontoons on the pond, supplemented by a land-based array of about 1,300 panels adjacent to the pond. Together, the array can generate 400 kWs at peak output, enough to offset the winery’s annual power usage and provide a net-zero energy bill.

-Federal Tax Incentive of 30% of the purchase price

-Annual energy costs offset by sending surplus energy back to the power grid

-System insulated from energy price hikes

-Accelerated depreciation

About one acre of vineyard was removed to accommodate the land-mounted portion of the system, but the floating array’s positioning on the pond saved another three-quarters of an acre of valuable Cabernet vines that would have been ripped out for a total land-mounted system. This is equivalent to about $150,000 worth of bottled Cabernet sales annually. Far Niente has just over 100 acres of vineyard.

Larry Maguire, Far Niente President and CEO, made it clear that the move to solar was not made for business or financial sense, but because it was the right thing to do from a social perspective. There is still a huge financial commitment involved, even after factoring in all the rebates, tax credits and other incentives. With conservative estimates of future electricity costs, Far Niente projects that it will take about 12 years for the construction costs of approximately $4.2 million to be offset.

|

|

| Land-based solar array in the foreground; floating array over irrigation pond in the back. |

The Green Story

The system prevents 927 tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) from being released into the atmosphere each year by fossil-fuel power plants. According to the U.S. Dept. of Energy, it takes 211 acres of trees one year to absorb that much CO2.

The Team

The project started in December 2005 when Far Niente brought in an energy consultant, Gopal Shanker of Recolte Energy of Calistoga. Late the next summer, California-based SPG Solar was selected as the system integrator and developed and installed the wineries’ solar system. Once Maguire’s partner, Dirk Hampson, suggested finding a solution to take advantage of the pond, SPG’s sister company, Thompson Technology Industries (TTI), stepped forward and said that it had developed, on paper, the technology to float an installation on water. And the Floatovoltaic system was born.

To represent the vineyard in the discussions with SPG and TTI, Maguire tapped Greg Allen, President of its Dolce brand, devoted to producing a single, late harvest wine, often used as a dessert wine. Allen’s story will ring a bell with many facilities managers, who for many years have learned what happens when top management discovers that somewhere along the way, the FM may have some expertise in something other than the job for which they were hired. See the sidebar for more on how Allen went from winemaker to solar project manager without missing a beat.

Challenges resulting from floating the solar array

Far Niente wanted to use as much of the surface of its irrigation pond as possible for the solar array. Taking into account the need to leave some space around the edges and that the banks of the pond were not straight everywhere, Far Niente was able to devote 80% of the pond to the array. The pond is approximately 240-feet square, and 11′ — 15′ deep.

Along the way, there were some special issues that needed to be addressed:

- Because positioning relative to the sun is so critical, there was concern that the panels would naturally float to different positions. This was addressed through use of articulating pontoons, so the panels would stay in the same relative position to one another.

- It was critical to ensure that the demand for water in the vineyard would be less than the supply, as a low pond would be a cause of concern.

- Special attention was devoted to accommodate any wind load, so that the pontoon units would not separate from one another.

- Since the system is effective only when the array is floating properly, there was concern that over the anticipated 25-year lifetime of the system, a pontoon may take on water or there may be some other reason for part of the array’s height to descend a bit. To this end, its height is monitored on a regular basis.

- Regular maintenance also had to be scheduled, to take care of dust and bird droppings (both prevalent around a vineyard and a pond). Allen estimates that twice a year is sufficient.

- Solar panels lose about 1% of their efficiency each year in converting from solar to electrical energy. So Far Niente made the installation a bit larger than it needed to be, so that it would generate the electricity needed toward the end of the projected life of the panels.

|

|

| Floatovoltaic solar array on pontoons over irrigation pond. |

One advantage from having the array mounted over the water (besides, of course, the saving of valuable vineyard) was that the panels shade the pond, keeping the water cooler in the hot, Napa Valley. Cool and shaded water presumably result in lower evaporative losses and therefore are very desirable for vineyards. Also, by being cooler than solar panels over the earth would be, Allen hypothesized that the solar panels over the water may generate more electricity per panel than the land-based panels. Allen said he should have enough information by the end of 2008 to know if this theory is valid.

Dealing with the unexpected

GREG ALLEN, PROJECT MANAGER AND PRESIDENT OF DOLCE

Greg Allen originally set out to earn a PhD in Mechanical Engineering. After collecting his B.S. in Mechanical Engineering, he worked as an engineer for the Department of Defense, living in the town of Napa, California. While there, he experienced his first visit to a winery, and started to get hooked. Nonetheless, he then went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to pursue his graduate degree. While there, a friend told Allen about an enology program at U.C. Davis. Eventually, Allen left MIT and went into the enology program, and the rest is history. And, oh yes, because Allen was a bright engineer, he got selected to represent Far Niente in managing the solar project.

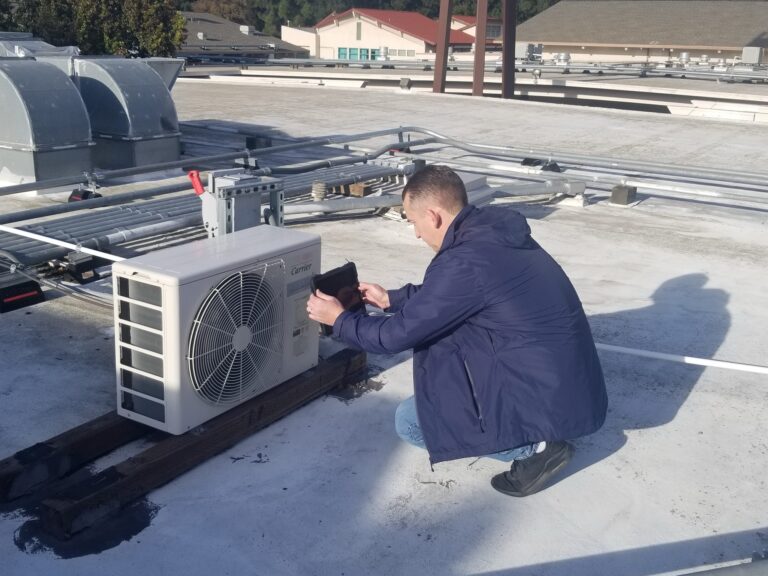

Most of the surprises for the solar project had to do with working with the local utility company, Pacific, Gas & Electric (PG&E). Because the traditional utility is set up with the purpose of providing energy in a regulated environment, the concepts of energy credits (and what it takes to measure, monitor and process them) and distributed generation (where the utility’s customers produce and supply electrical energy to the grid) are new ones that don’t easily fit into the mold of a regulated utility. So both sides needed to go back and forth many times, sometimes causing delays, and sometimes causing new equipment to be purchased. Even something as seemingly simple as access by the utility company to its service transformer on the property was an important factor that significantly affected project complexity and led to cost overruns. Having a consultant who has been through the process with the local utility company was essential, as was a progressive utility that strongly wants to be supportive of solar power, but it wasn’t always enough.

It also is important to be sure that all meters and transformers are approved by the utility company in advance. Sometimes, in order to comply with its requirements, it may not be possible to do what makes most economic sense, even for something as seemingly simple as connecting to the utility meter.

PG&E was concerned that on low-demand days, the connection to the grid would result in too much energy being generated. Far Niente thus had to upgrade its service transformer, which not only cost time and money, but it had to go through state and local permitting processes again.

Results to-date

Prior to commencing the project, Allen estimated the following breakdown of its electrical consumption:

- “Typical” electrical (mostly lighting)-37%

- HVAC (mostly air conditioning)-13%

- Refrigeration plant (for wine)-29%

- Other production-19%

- Other-2%

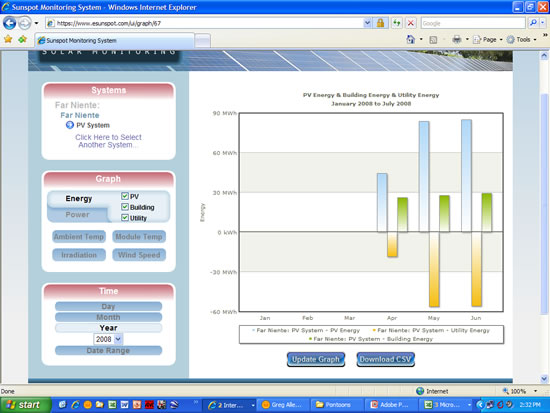

The system’s electricity production is monitored in real-time by SunSpot©, a proprietary monitoring software and hardware system made by TTI. The chart below shows that for each month that the system has been in operation, starting with the partial month of April, the solar system has generated far more energy (first bar on graph for each month) than Far Niente required (second bar), leaving a net surplus (third bar). Since monitoring started in April, through June 30 Far Niente has generated 80,345 kWh more than it has consumed (135,002 kWh).

Far Niente accumulates its credit over the course of the year, so the credits earned over the summer will be needed to compensate the expected lower amounts of energy generated during the shorter winter days. With PG&E, the account is settled once each year (as opposed to the more traditional monthly utility bill). Spring is an ideal time to begin harvesting the sun’s abundant energy. The relatively large credit currently showing for Far Niente may seem excessive, but to date, the system’s performance is on track for providing a net-zero energy bill at the end of its first year of operation, which will be after the lean solar winter months.

|

|

| Far Niente has generated a significant energy surplus (last bar shown for each month) during the initial three months of operation. The SunSpot© monitoring system was developed by TTI and installed by SPG Solar. Reproduced with permission. |

Beyond solar

It should be noted that the solar solution is not the only sustainability solution employed by Far Niente. Maguire said, “We will always be committed first and foremost to producing great wines . Yet, we recognize that our environment is facing significant challenges, and we [must] do our part and take sustainable measures where possible.” To this end, Far Niente employs sustainable and organic farming, powering farming vehicles with biodiesel fuels, recycling, the use of hybrid company vehicles, and other environmentally responsible measures.

Far Niente was founded in Oakville, California in 1885 and prospered until the onset of Prohibition in 1919, when the winery was abandoned. Gil and Beth Nickel revived the winery in 1979, restoring the estate to its original grandeur—today, its gardens are among the most beautiful in the entire Napa Valley. Far Niente introduced sister wineries, Dolce and Nickel & Nickel in 1989 and 1997, respectively.