Paying lip service to safety

For too long, provision for safety has been the white elephant in the room for developers, designers, contractors and endusers. Ashford Pritchard asks whether owners and clients are doing enough to protect the workers who build their facilities.

|

Shocking, appalling, and horrific are adjectives that describe both several recent highly publicised site accidents and Hong Kong’s general construction safety record. The images live long in the mind. A collapsed crane astride a building in global retail centre Causeway Bay, an injured worker being rushed from a prominent university following the botched demolition of a wall. Yet behind the attention-grabbing headlines, the figures are equally startling.

need for improvement

In 2007, Labour department statistics show, there were 19 fatalities and 3,042 industrial accidents attributable to the construction industry. This year already, anecdotal evidence suggests up to 14 fatalities. To put these figures in perspective, the Hong Kong Police recorded 18 homicides and 8,000 serious assaults last year. With strenuous physical requirements and hazardous environments, it’s a foregone conclusion that construction is always going to be a dangerous industry. However, argues Steve Grant, Director, ProjexAsia: “If people really think carefully and plan properly, it is possible to have zero accidents.”

|

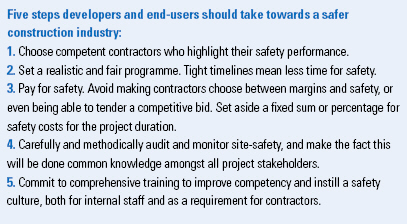

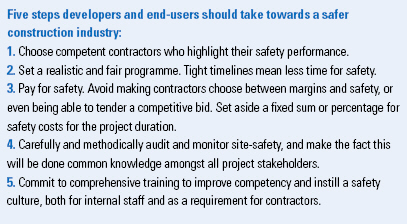

He should know. Following an incident a few years ago when one of his workers was seriously injured, Grant put safety at the forefront of his company’s operations. By initiating comprehensive training schemes and procedures that have instilled a safety culture among his teams, he can say that no serious accidents have occurred to his site workers since. Picking up several safety awards over the past few years, he is also involved in driving the Safety Task force of the British Chamber of Commerce Construction Industry Group (BCC CIG). If one contractor can have a stellar safety record, surely it is possible for all, he believes. However, under the “lowest price wins” approach favoured by many developers, contractors and subcontractors such as Grant face intense competition on cost, which in turn affects the amount of budget that can be allocated to safety.

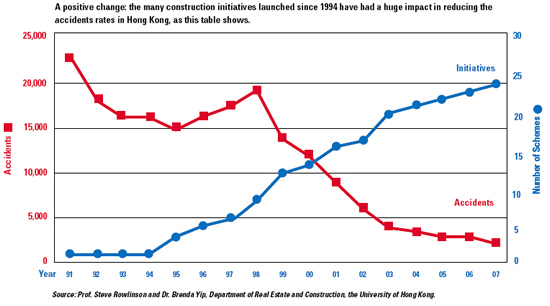

Perhaps indicative of the sensitivity of the construction community to this fact, when asked about the role endusers and developers have to play, Keith Kerr, Chairman of the Construction Industry Council (CIC) and Managing Director, Swire Properties, says: “It is too complicated an issue to make short, snappy comments. All I would say is that site safety is a priority issue for CIC and is the subject of a CIC committee. A number of initiatives are already underway and undoubtedly more to follow.” While initiatives such as these have a significant impact in the number of accidents shown (see table p34), the question of whether the clients behind construction projects are helping or hindering safety is one that cannot be answered so easily. “The developer is of central importance to the safety performance on a project,” believes Dr. Brenda Yip, Department of Real Estate and Construction, Hong Kong University. She cites the varying accident records of contractors working on projects for different developers, highlighting that certain developers play an active role in promoting safety on site. Professor Steve Rowlinson, Department of Real Estate and Construction, Hong Kong University, agrees, adding: “There are perhaps four of five developers in Hong Kong who focus on safety and are prepared to pay for it.” He cites the Housing Authority as a prime example. In the late 90s a policy of extending contract durations by two months was initiated, with an emphasis on improving safety and quality. In the early 00s a comprehensive study on accident causes was undertaken, and while not all measures are still being continued today, there is the clear emphasis on safety you would hope to find in a public body.

|

For private developers, profit is clearly the first priority. A lack of guidance from the government puts safety squarely in their court. “In Hong Kong, unlike the UK or Australia, you have neither code of practice nor legislation,” Rowlinson points out. This framework-free market, coupled with the predominance of competitive procurement strategies, means that margins are being squeezed on all levels of projects. In a costcutting climate, with first-past-the-post competitive tendering, safety tends to fall by the wayside. “There’s no way to safeguard safety, not in an industry where you’ve got margins of one percent,” Rowlinson emphasises. Both Rowlinson and Grant mention that a “Pay-for-safety” approach, whereby a fixed percentage of contract sums are required to be ringfenced for safety, has been proven successful in mitigating much of the current problems.

Money, and the pursuit of profits at the cost of people, is at the heart of the safety question. “Developers are seen as being greedy and gluttonous in making big bucks out of a construction project whereby little of the profit so earned is spent on improving site safety,” says Michael Leung, President, Society for Registered Safety Officers. He unhesitatingly offers a long and comprehensive list of reasons why construction leads the way for workplace accidents, covering everything from the way the industry is structured to the on-site role of the safety officer.

|

a short term view

At the heart of all these reasons, says Leung, is the short term view taken towards the importance of safety on-site. This can be seen at all levels from the money men at the top who under-value the added quality benefits from paying for safety, to the on-site workers who take risky shortcuts that put themselves in harm’s way. Also clearly evident is a lack of leadership and guidance from the government on something that is becoming, in effect, a public health issue. The scope for government innovation and involvement is wide. The government should be more vigilant in the enactment and enforcement of site safety laws and standards, says Leung. For example, on an issue as straightforward as site-safety monitoring, safety inspectors should be required to be employed by the client, developer or consultant instead of by the contractor, “so that the safety officers can really perform their role as a watchdog on site safety.” Professor Rowlinson also highlights the importance of availability of information. “The Labour department should publish tables to show who the best contractors are and who the best developers are in terms of number of accidents.” Insurance companies could also help. Instead of keeping individual client data secret, by creating cross-industry ratings and adjusting premiums for developers and contractors accordingly, they could add a much needed financial imperative for change.

After all, it seems clear that money talks loudest when it comes to developer decision making, even when safety is at stake.

|

life-cycle approach

But at the end of the day, for real change to happen the entire industry needs to take the challenge of safety onboard. “There has to be a whole life-cycle approach, it’s not just the construction process, often the designers are creating features that make a building impossible to maintain safely,” says Rowlinson. Beyond the clear facility management implications, the design and planning of construction itself also has a pivotal impact on safety. Studies show that up to 60 percent of accidents could have been avoided before the project got to the site, common mistakes include poor material sourcing and handling, project scheduling and many more. One innovative response to the need for developers and end-user clients to drive safety improvements is a noteworthy initiative by the Australian government’s Federal Safety Commissioner. As part of a move “to achieve world-class occupational health and safety (OHS) in the building and construction industries,” a set of guidelines have been created to guide those who are willing to place safety at the heart of their projects.

This Model Client Framework is a step-by-step process with clear guiding principles and covers all stages of the construction and development process. The framework explains how developers and end-users are essential if there is going to be a real improvement of safety in the industry. As the framework documentation says: “Model clients play a key coordination role in ensuring that OHS issues are managed and information is shared throughout the construction supply chain. As the drivers of projects and as purchasers of the building and construction industry’s services, model clients are in the best position to drive the cultural change needed to bring about improvements in OHS in the building and construction industry.” Given the frankly shocking safety record of the construction industry, it is clear that there is a need for continued improvement in how we design, build and commission our built environment. Preventable accidents are occurring every day. Beyond being just the backers and controllers of projects, developers and end-users are those who will eventually benefit the most from the space being constructed. The buck must stop with them when it comes to safety on their projects. As the accident rates show, there is sadly still much room for improvement.

|

| Some large contractors are now beginning to achieve incident rates (IRs) comparable with countries such as the UK, Canada & Australia. However, the renovation, maintenance, addition and alternation (RMAA) sector accounts for a large percentage of construction related deaths and accidents in Hong Kong. |

A contractor’s view

Gammon Construction’s Derek Smyth, Executive Director and Dean Cowley, Senior Safety Manager.

What should end-users and developers be doing to ensure safety on their projects?

During the design and construction phase, end-users should be giving adequate consideration and planning to the persons who will be using the end product, questioning whether the building or facility will be safe to use. In this respect more can be done to follow examples such as the UK’s Construction Design Management (CDM) regulations. Following models such as these would ensure that developers and end-users are more involved in the decision making process on “buildability” (whether the building or end product can be built safely and work safely for the maintenance works after occupation.)

With a very few exceptions, the private sector approach to safety still remains woeful, with the majority of clients and developers remaining not very interested or committed to safety. Clients and developers need to visibly show care and concern for safety, and fully recognise they have a “duty of care” when it comes to the safety of the workforce constructing their buildings. Their main decision making criteria should not be price driven alone.

Is construction just more dangerous by nature or is the industry underperforming on safety?

Undoubtedly, construction is a very high-risk industry, and the fact that we work in a very high-risk industry is widely recognised by all. This itself is problematic, as construction industry workers and management’s “risk perception” has arguably been reduced through continual exposure. In some cases a very blase attitude towards managing risks has evolved. We need to revisit, enhance and educate all in the way in which we view risk, and most certainly the way in which we manage safety.

Arguably Hong Kong as a whole, whilst showing some steady signs of improvement within the industry statistics over the past 10 years, still has some way to go. Some large contractors are now beginning to achieve incident rates (IRs) comparable with countries such as the UK, Canada & Australia. However, the renovation, maintenance, addition and alternation (RMAA) sector accounts for a large percentage of construction related deaths and accidents in Hong Kong, making this arguably the more problematic area, something that needs to be addressed.

There are also many, many other contributory factors, such as an ageing workforce (65 percent of workers are over 40 and 32 percent over 50), very demanding climatic conditions, quality of training and supervision and cost cutting.

How much is cost cutting (from all parties) hampering safety improvements? Is this mainly the fault of endusers and developers, or is this something where everyone is equally to blame?

This is a major issue within the industry. The procurement process in HK is fraught as it is totally cost driven. The end result is all too often cost cutting throughout the organisation and ultimately at the frontline by the sub-contractors. As a result of an increasingly competitive market, and diminishing profit margins, main contractors are forced to take on the cheapest sub-contractors, who in turn need to cut costs to win the work. Equally diminishing profit margins usually mean there is inadequate budget and resources for health and safety (H&S).

The main contractors provide the majority of the resources and budget for H&S, and arguably do not do enough to lobby their customers to give them sufficient allowances for adequate safety resources. Tight, unrealistic programmes are also a big issue, which further compound this problem between the clients and contractors. There was a Safety Partnering Programme initiated within the private sector, which commenced in 2005 for the developers to set up an incentive scheme (or “pay for safety” scheme) for the main contractors in relation to safety issues. However, not too many clients are willing to participate in this Safety Partnering Programme because they still consider price to be their major concern and no private sector site has joined the Programme in the last nine months, a strong indication of their level of commitment.

For more information on the model client framework, visit www.fsc. au/ofsc/Otherinformation/Publications/ ModelClientpublications.htm