by Jenn Shelton — This article originally appeared in the September/October 2021 issue of FMJ

For more than a year, facility management has been a key focus of executive discussions. The COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath has placed increased demands on the profession and called into question the future of corporate real estate. Practitioners now face crucial decisions in strategic leadership and managing competing interests as many organizations transition to hybrid working models. The traditional corporate workplace is undergoing a paradigm shift, and the balanced scorecard can help to navigate the route to the new model of work.

In the time since COVID-19 was declared a public health emergency, the global pandemic has forced corporate office shutdowns and reopenings, layoffs and rehiring. FMs found themselves on the frontline of managing pandemic containment and mitigation — doing the critical work of protecting essential staff, tenants and visitors from the deadly virus.

As vaccination rates begin to approach herd immunity, however, the future of CRE has become uncertain. Some organizations are eschewing offices entirely and going fully remote. Others are insisting upon a return to the pre-pandemic onsite working model. According to Deloitte’s survey of 275 executives in April 2021, 68 percent plan to implement some kind of hybrid model, 21 percent plan to return to physical workspaces, 10 percent are still undecided, and 1 percent plan to remain remote. Furthermore, EY’s 2021 Work Reimagined Employee Survey reports that 54 percent of employees “would consider leaving their job post-COVID-19 pandemic if they are not afforded some form of flexibility in where and when they work.” For its part, the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) anticipates that the hybrid work model will be the new norm.

ISO 41011 defines FM as an “organizational function which integrates people, place and process within the built environment with the purpose of improving the quality of life of people and the productivity of the core business.” What, then, does the new hybrid model mean for the FM profession?

FM is at an inflection point

With change comes opportunity. As hybrid working increases the demands on FMs, it also offers the chance for FM leaders to have a more strategic impact on organizations they serve. In their book Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works, A.G. Lafley and Roger Martin describe strategy as an integrated cascade of choices:

winning aspiration > where to play > how to win > capabilities in place > support systems

In this model, it becomes clear that in Workplace 2.0, FM has moved upstream from being a support system for strategy to being part of the set of capabilities in the strategic arsenal, and — depending upon the nature of the business — potentially being a key part of an organization’s winning value proposition and competitive advantage. FM’s challenge is to build a tool, a framework to get started — one that will balance the competing demands of customers, finance, operations, human resources, and innovation, and tie them to the vision, values and strategy of the organization. That tool is the balanced scorecard.

What is a Balanced Scorecard?

The balanced scorecard is a strategic framework that emerged in the early 1990s and was most famously popularized by Robert Kaplan and David Norton in their 1992 Harvard Business Review article, “The Balanced Scorecard — Measures That Drive Performance. In 1996, the authors expanded their ideas into a bestselling business book, The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action. At one point, the framework was in use at half of Fortune 1000 companies, and it was hailed by the Harvard Business Review as one of the 75 most influential ideas of the 20th century.

Kaplan and Norton argued that the Information Age had obsolesced performance management assumptions from Industrial Age. They asserted that the use of financial control systems and metrics alone could no longer accurately guide investment or lead to sustainable competitive advantage. Instead, Kaplan and Norton maintained that the Information Age required new capabilities beyond capital and technological investment — organizations needed to mobilize and exploit their intangible assets as well, which would enable them to:

- Develop customer relationships;

- Introduce innovative products and services;

- Produce customized high-quality products and services;

- Mobilize employee skills and motivation; and

- Deploy information technology, databases and systems.

The balanced scorecard was therefore a synthesis of the legacy historical-cost financial accounting model and modern assessments of long-range competitive capabilities. In other words, it included both financial metrics and the elements that propel this performance.

The right tool for a hybrid workplace transformation

Today’s FMs find themselves at a similar crossroads. Information technology has made great strides in digitizing the real estate industry, and Proptech companies are attracting increasing attention and investment from VCs. Verdantix predicts that the smart buildings market (which includes property management, IWMS, CAFM, CMMS as well as energy management, real estate investment and space utilization solutions) will grow from US$6.4B in 2021 to $8.5B in 2025. Moreover, the hybrid workplace model is forecast to accelerate the pace of this digital transformation, obsolescing systems and metrics predicated entirely on an on-site working model. As employees gain more choices in where, how, and when they work, not only will corporate real estate supply outstrip demand, but that demand is likely to become increasingly sophisticated and specialized.

Multiple reports indicate that executive leadership teams are already reassessing their real estate investments. In a survey of 248 U.S. chief operating officers, McKinsey found that fully one-third of respondents plan to let their leases expire. Consequently, competitive pressure will increase on CRE professionals to demonstrate a clear workplace experience value proposition for their occupants. Managing properties entirely by control systems and operational metrics will no longer be a sufficient measure of success. A balanced scorecard will help FMs monitor this data in addition to leading indicators of performance and competitive advantage, thus providing a framework to enhance occupant relationships, introduce innovative services, be agile and cost-competitive, and optimize staff and resource utilization.

A dashboard for cross-functional focus and alignment

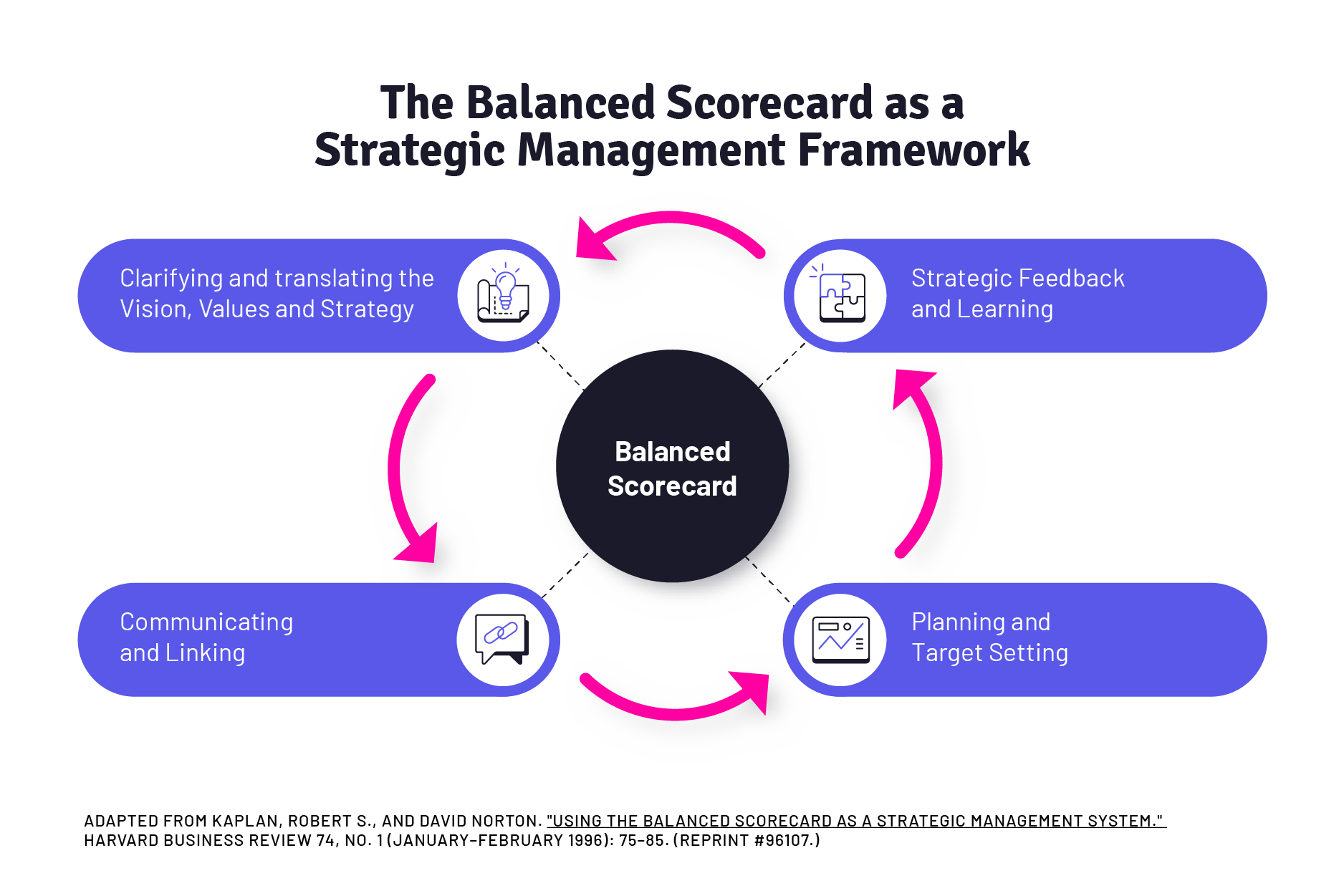

A hybrid workplace transformation necessarily involves collaboration among different departments, including FM. Efforts must be coordinated with human resources, operations, IT and project management. Interaction may also be required with legal and risk management SMEs. It is therefore reasonable to assume that building a balanced scorecard for the hybrid workplace will require FMs to orchestrate a harmonized strategy with these groups. The balanced scorecard will provide a strategic management framework to clarify, communicate, plan and review key initiatives involved in the new model of work — ones which will drive the organization forward to sustainable competitive advantage.

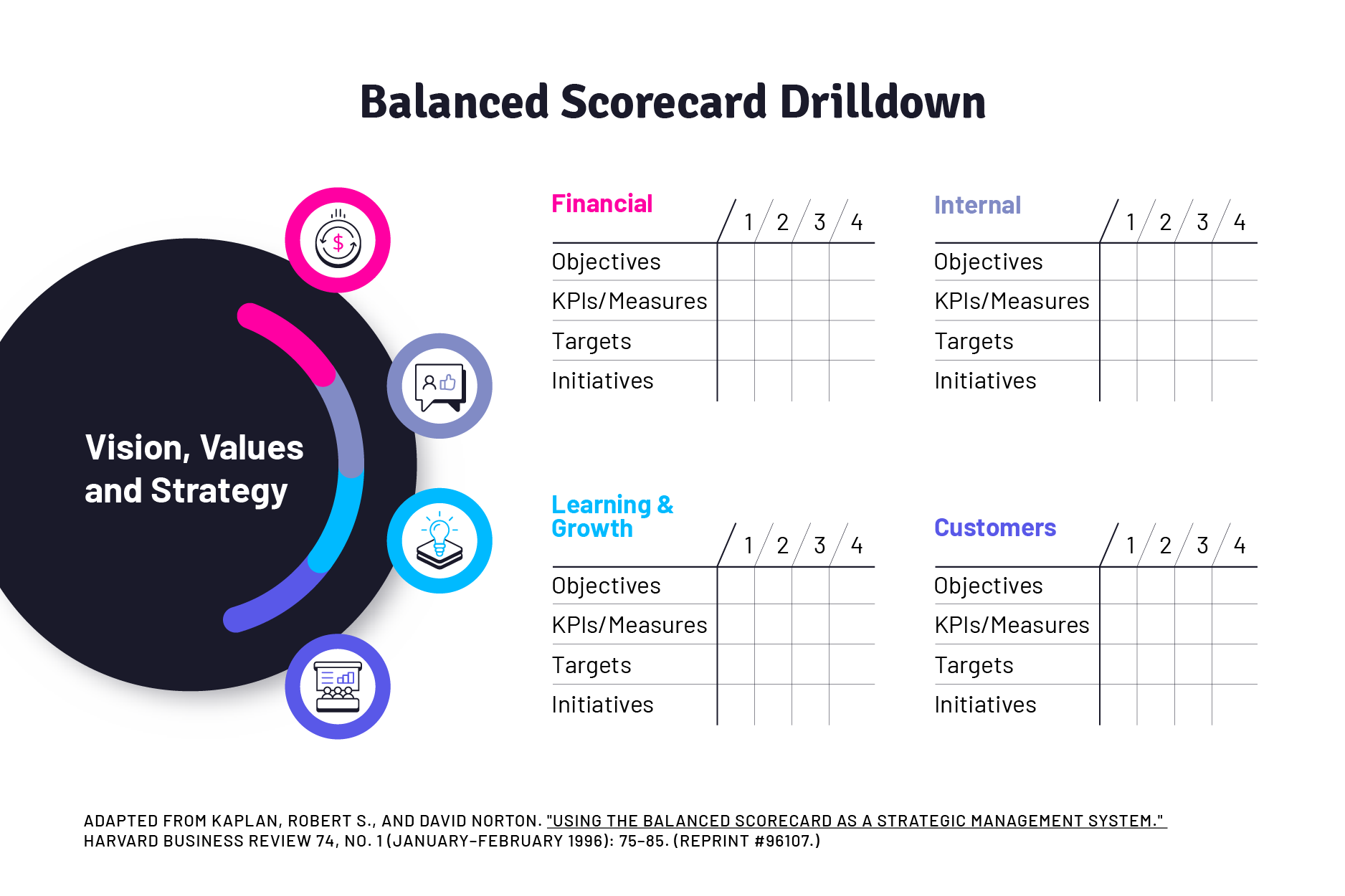

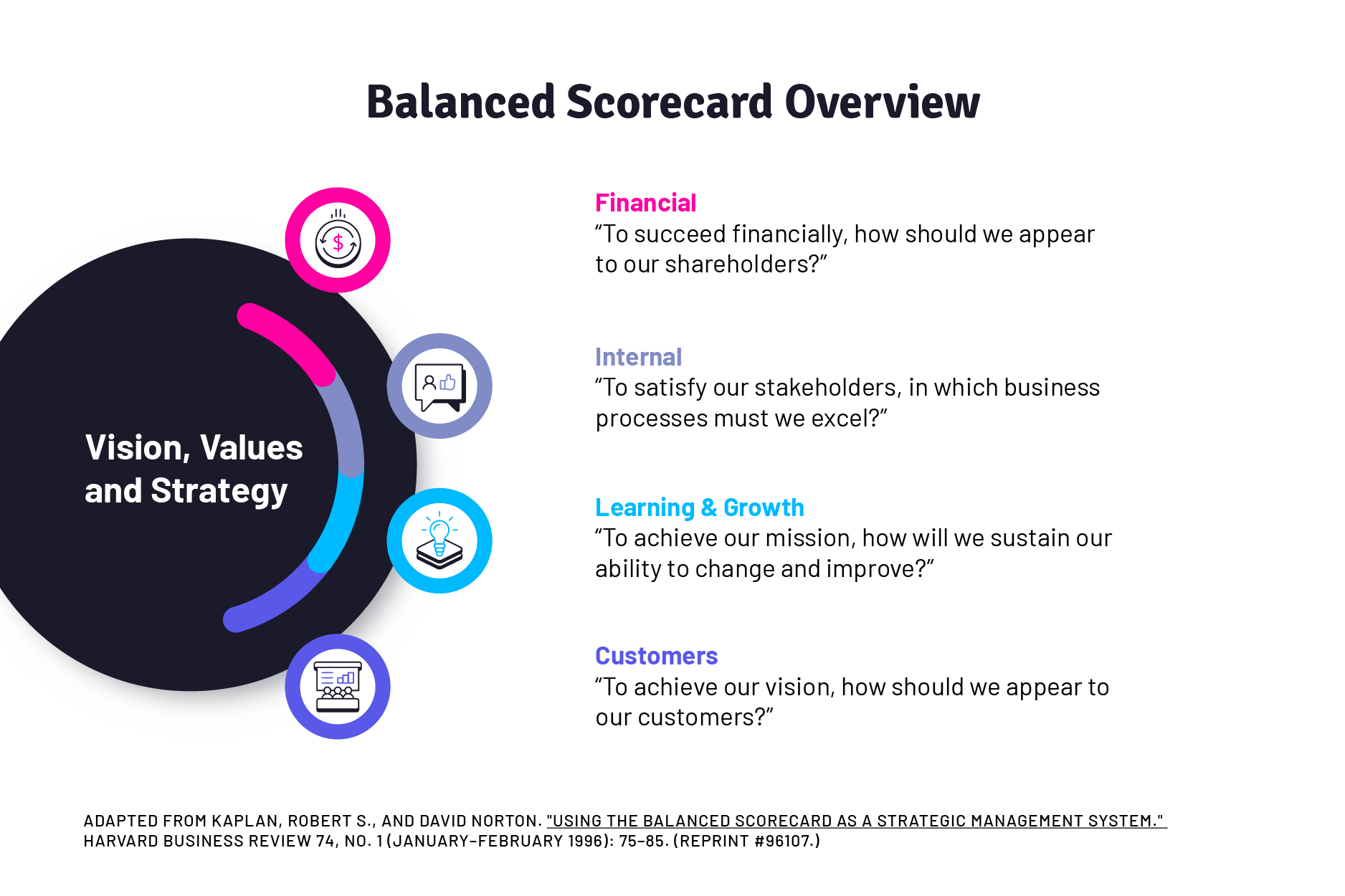

As shown in the figure below, the balanced scorecard examines an organization from four perspectives: financial, customers, internal processes, and learning and growth. Consider it a strategic dashboard for the journey to the hybrid working model. Its central compass is the organization’s vision, values and strategy, and the four quadrants provide instrumentation to navigate and monitor progress on the journey to hybrid transformation. It can be used to communicate goals, set priorities, align daily operations with strategy and monitor progress towards these strategic milestones.

The balanced scorecard provides a platform for shared understanding, not only horizontally across disciplines, but also vertically from business units, to teams, to individuals. “Cascading” a balanced scorecard means disaggregating its objectives, measures, targets and initiatives down through the organizational hierarchy, with each departmental and team scorecard focusing on the objectives and measures that drive high-level strategic goals. This enables all levels of the organization to understand the consequences of decisions, the drivers of long-term success and the balance between objective and subjective measures. It also provides a rationale to allocate resources and link rewards to performance measures.

The balanced scorecard provides a platform for shared understanding, not only horizontally across disciplines, but also vertically from business units, to teams, to individuals. “Cascading” a balanced scorecard means disaggregating its objectives, measures, targets and initiatives down through the organizational hierarchy, with each departmental and team scorecard focusing on the objectives and measures that drive high-level strategic goals. This enables all levels of the organization to understand the consequences of decisions, the drivers of long-term success and the balance between objective and subjective measures. It also provides a rationale to allocate resources and link rewards to performance measures.

Building the Balanced Scorecard

Here is a brief overview of the parts of the balanced scorecard and how these might be employed in a hybrid workplace transformation:

Vision, Values and Strategy

Corporate FMs are likely to be well-versed in the strategy framework outlined in ISO 41014:2020, however, this is not the kind of strategy to which the balanced scorecard refers. Rather, it denotes an overarching corporate strategic imperative, one which the hybrid transformation strategy must support. In Lafley & Martin’s Playing to Win, it is a statement that encapsulates the answers to the following questions:

- What is your winning aspiration? The purpose of the enterprise, its motivating aspiration.

- Where will you play? A playing field where this aspiration can be achieved.

- How will you win? What it takes to win on the chosen playing field.

This strategy must be supported by a set of values, ethics or principles that underpin decision-making, and which will inform the new model of work.

Financial

“To succeed financially, how should we appear to our shareholders?”

As the name implies, the financial section of the balanced scorecard examines an organization’s monetary performance and the use of its financial resources. It measures whether actions already taken have contributed to bottom-line improvement by raising revenues, lowering costs and improving asset utilization.

Examples of important goals in a hybrid workplace context might include:

- Generating revenues from new hybrid workplace services such as subleasing;

- Taking advantage of demand-based resource allocation to reduce costs such as labor, rent, property taxes, furniture, equipment, supplies, insurance and other expenses;

- Increasing space utilization; and

- Shifting spending from capital expenditures to operating expenditures.

Customers

“To achieve our vision, how should we appear to our customers?”

This section of the balanced scorecard views performance from the perspective of the customer or key stakeholders the organization is designed to serve. From an FM lens, these could be building tenants, occupants or their customers. FMs would benefit from working with the business to determine how the new model of work could help to drive the following customer or stakeholder goals:

- Increasing customer/stakeholder acquisition, satisfaction, retention and profitability;

- Improving quality/efficiency of the services and solutions delivered;

- Growing market and account share; and

- Increasing brand equity via workplace experience.

Internal

“To satisfy our stakeholders, in which business processes must we excel?”

The internal process section of the balanced scorecard evaluates the quality and efficiency of an organization’s performance related to the product, services, or other key business processes at which it must excel. It will necessarily be specific to a given industry and organization. When considering how the hybrid workplace transformation affects internal operations, FMs should align with business partners on the strategic goals for:

- Improving operational excellence via process innovations such as just-in-time workspace provisioning, cleaning, and maintenance;

- Enhancing environmental, social and governance (ESG) capabilities such as

- Reducing waste, as well as energy and water consumption,

- Ensuring equity in labor practices for remote and onsite staff,

- Providing accountability and transparency in hybrid working practices; and

- Reducing operational risks from hybrid work and staying compliant with changing local guidelines and increasing onsite and virtual health, safety and security measures.

Learning & Growth

“To achieve our mission, how will we sustain our ability to change and improve?”

The Learning and Growth section of the balanced scorecard reflects organizational capacity and consists of human capital, infrastructure, technology, culture and other elements that contribute to breakthrough performance. It requires practitioners to develop a hypothesis about the future of the organization and how to get there. For example, from an FM perspective, the hybrid work model changes the definition of “the workplace” and may therefore change the mandate of the role.

Practitioners should anticipate the need for strategies that involve:

- Creating a vision for employee experience (EX) in a hybrid work environment that will be a blend of the real and virtual workplace;

- Improving customer satisfaction and success via a strong and unified online and onsite customer experience (CX) that leverages, enhances and extends the organization’s brand equity;

- Introducing new core competencies and skills development strategies that are location and time-zone agnostic; and

- Investing in information systems that accelerate and support all the initiatives on the balanced scorecard (e.g. digital twin, IWMS, IoT, etc.).

The balanced scorecard is one of the most recognized strategic frameworks of the past 25 years, and it is well-suited to the challenge of a hybrid workplace transformation. It has been used successfully as a performance management tool in a wide variety of organizations that face the challenge of addressing competing perspectives during times of flux. It offers a clear reporting dashboard that gives structure to the tangible and intangible elements involved, and it provides a platform for discussion and alignment among the key stakeholders who are creating the new model of work. In addition, the balanced scorecard drills down from vision to activity, thus linking individual goals to the overall transformation objectives. Finally, it provides a context for these efforts.

Nevertheless, the task of building a balanced scorecard can seem overwhelming at first. There are no shortcuts or templates. Each organization’s scorecard is unique to its situation — its industry, market, segment and strategy. There may be voluminous data to collect, as each dimension has multiple objectives and key results (OKRs) to measure and evaluate. It may also require significant cultural change to get started. Fortunately, there are mitigating steps which FMs can take to ensure successful adoption of the balanced scorecard. The first is to find an executive champion who can sponsor the change efforts, encourage buy-in and help the project gain momentum. The second is to start small, iterate in an agile manner, and be responsive to feedback as the implementation progresses.

The balanced scorecard’s success has been attributed to its flexibility and suppleness, which has allowed it to evolve and stay relevant over decades. It connects support systems and the capabilities they enable to the winning aspirations of organizations. By taking this strategic approach, FMs can demonstrate their value, act as trusted advisors and contribute to the success of their organizations during this unprecedented time of change.

About the Author

Jenn Shelton is Product Manager, Innovation, at IBI Group, a technology-led architecture, engineering, and design firm. Shelton is a certified scrum master and holds an MBA and a masters of education in workplace learning and change from the University of Toronto.

Jenn Shelton is Product Manager, Innovation, at IBI Group, a technology-led architecture, engineering, and design firm. Shelton is a certified scrum master and holds an MBA and a masters of education in workplace learning and change from the University of Toronto.

Footnotes:

Stoller, K. (2021, April 20). Never Want To Go Back To The Office? Here’s Where You Should Work. Forbes. forbes.com/sites/kristinstoller/2021/01/31/never-want-to-go-back-to-the-office-heres-where-you-should-work/?sh=7953b7686712.

Ritter, M. (2021, June 21). Here are the companies rushing workers back to the office – and the ones that aren’t. CNN. cnn.com/2021/06/19/business/return-to-office-company-policies/index.html.

Pearce, J. (2021, June 11). 2021 Return to Workplace Survey. Deloitte US. Deloitte United States. www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/human-capital/articles/2021-return-to-workplace-survey.html.

Global, E. Y. (2021, May 12). More than half of employees globally would quit their jobs if not provided post-pandemic flexibility, EY survey finds. EY. ey.com/en_gl/news/2021/05/more-than-half-of-employees-globally-would-quit-their-jobs-if-not-provided-post-pandemic-flexibility-ey-survey-finds.

Gurchiek, K. (2021, January 27). Hybrid Work Model Likely to Be New Norm in 2021. SHRM. shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-news/pages/hybrid-work-model-likely-to-be-new-norm-in-2021.aspx.

International Organization for Standardization. (n.d.). ISO/TC 267 Facility management. International Organization for Standardization (ISO). committee.iso.org/home/tc267.

Lafley, A. G.; Martin, R. L. (2013). Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works. Harvard Business Review Press.

Kaplan, R. S.; Norton, D. P. (1992). The Balanced Scorecard – Measures That Drive Performance. Harvard Business Review (January–February): 71–79.

Kaplan, R. S.; Norton, D. P. (1996). The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy Into Action. Harvard Business School Press.

Niven, P. (2002). Balanced Scorecard Step-by-Step: Maximizing Performance and Maintaining Results. John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2002. p.12.

Kaplan, R. S.; Norton, D. P. (1996). The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy Into Action. Harvard Business School Press. p.3.

Derven, R.; Foster, M. (2018). CRE Tech Adoption Speeds Up. NAIOP Commercial Real Estate Development Association. naiop.org/Research-and-Publications/Magazine/2017/Winter-2017-2018/Business-Trends/CRE-Tech-Adoption–Speeds-Up.

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2020). Powering digital transformation through proptech. Emerging Trends in Real Estate® 2020. pwc.com/ca/en/industries/real-estate/emerging-trends-in-real-estate-2020/digital-transformation-proptech.html.

Donati, A. K. (2021, January 10). Proptech And Contech VCs Predict What Is In Store For 2021. Forbes. forbes.com/sites/angelicakrystledonati/2021/01/10/proptech-and-contech-vcs-predict-what-is-in-store-for-2021/.

Trinquet, J.; Clarke, S. (2021, January 29). Smart Buildings Software: Market Size And Forecast 2020-2025 (Global). Verdantix. research.verdantix.com/report/smart-buildings-software-market-size-and-forecast-2020-2025-global.

Lund, S., Madgavkar, A., Manyika, J.; Smit, S. (2021, March 3). What’s next for remote work: An analysis of 2,000 tasks, 800 jobs, and nine countries. McKinsey & Company. mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/whats-next-for-remote-work-an-analysis-of-2000-tasks-800-jobs-and-nine-countries.

Niven, P. R.; Lamonte, B. (2017). Objectives and key results: driving focus, alignment, and engagement with OKRs. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Bible, L., Kerr, S.G., & Zanini, M. (2006). The Balanced Scorecard: Here and Back: From Its Beginnings as a Performance Measurement Tool That Looked beyond the Traditional Financial Measures, the Balanced Scorecard Has Evolved into an All-Encompassing Strategic Management and Control System. Management Accounting Quarterly, 7, 18. p.22.

International Organization for Standardization. (2020, September 9). ISO 41014:2020 Facility management — Development of a facility management strategy. ISO. iso.org/standard/68170.html.

Lafley, A. G.; Martin, R. L. (2013). Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works. Harvard Business Review Press.

Bible, L., Kerr, S.G., & Zanini, M. (2006). The Balanced Scorecard: Here and Back: From Its Beginnings as a Performance Measurement Tool That Looked beyond the Traditional Financial Measures, the Balanced Scorecard Has Evolved into an All-Encompassing Strategic Management and Control System. Management Accounting Quarterly, 7, 18. p.23.