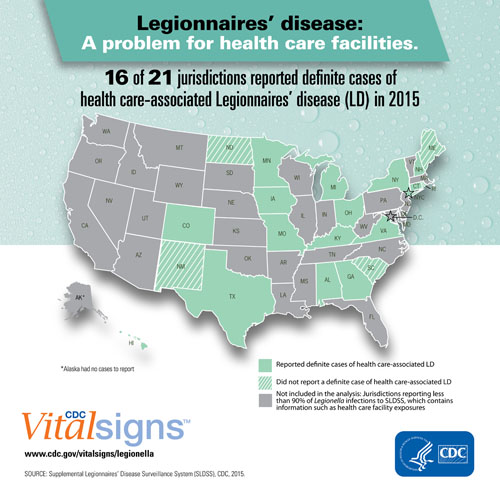

by Brianna Crandall — June 30, 2017 — An analysis released earlier this month by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that among the 21 U.S. jurisdictions studied, 76 percent reported health-care-associated cases of Legionnaires’ disease, a concerning finding since Legionnaires’ disease acquired from health-care facilities can be particularly severe. The findings highlight a possible greater risk of fatality for patients who are exposed to Legionella in health-care facilities.

According to the CDC Vital Signs report, Legionnaires’ disease is a serious lung infection (pneumonia) that people can get by breathing in small droplets of water containing Legionella bacteria. Legionella can make people sick when they inhale contaminated water from building water systems that are not adequately maintained, points out global building technology society ASHRAE in a response to the report.

While most cases of Legionnaires’ disease are not associated with health-care facilities, one in four people who get the infection from a health-care facility will die. This death rate is higher than for people who get the infection elsewhere, such as hotels or convention centers, noted the report.

The findings are based on exposure data from 20 states and New York City; the analysis was limited to these 21 jurisdictions because they report exposure information. This was used to see how often Legionnaires’ disease was associated with health-care facilities. Findings indicate that 3% of Legionnaires’ disease cases are “definitely associated with a health-care facility,” and an additional 17% are “possibly associated with a health-care facility.”

CDC Acting Director Anne Schuchat, M.D., stated:

Legionnaires’ disease in hospitals is widespread, deadly, and preventable. These data are especially important for health-care facility leaders, doctors, and facility managers because it reminds them to think about the risks of Legionella in their facility and to take action. Controlling these bacteria in water systems can be challenging, but it is essential to protect patients.

Among the Legionnaires’ disease cases “definitely associated” with health-care facilities:

- 80% were associated with long-term care facilities, 18% with hospitals, and 2% with both

- Cases were reported from 72 unique facilities, with the number of cases ranging from one to six per facility

- 88% were in people 60 years of age or older

Nancy Messonnier, M.D., director of CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, noted:

Safe water at a health-care facility might not be on a physician’s mind, but it’s an essential element of health-care quality. Having a water management program that focuses on keeping facility water safe can help prevent Legionnaires’ disease.

Michael Patton, member of ASHRAE Committee SSPC 188, stated in response to the report:

Determining Legionnaire’s disease causation is not simple since the mere presence of Legionella in a water system or device is not sufficient to cause disease. The bacteria must ultimately be inhaled or aspirated into the lungs of a susceptible person to cause disease. Since people with conditions that have reduced their ability to fight off infections are especially susceptible, it is not a surprise the report found patients in health-care facilities to be at risk. It’s vitally important all buildings incorporate good design, operations and maintenance procedures that prevent growth and spread of Legionella as these are regarded as the best methods of preventing disease.

What can facilities managers do?

According to ASHRAE, the incorporation of a Water Management Plan will reduce the chance of heavy colonization, amplification and dissemination to people. With this in mind, the organization developed ASHRAE Standard 188: Legionellosis: Risk Management for Building Water Systems to assist designers and building operators in developing a Water Management Plan that includes practices specific to the systems that exist in a particular building, campus or health-care facility.

To date, more than 5,000 copies of ASHRAE Standard 188 have been purchased. It can be previewed at no cost on the ASHRAE Web site.

Based upon this ASHRAE standard, the CDC developed a toolkit entitled “Developing a Water Management Program to Reduce Legionella Growth and Spread in Buildings: A Practical Guide to Implementing Industry Standards.” The document — initially released in 2016 and updated on June 5 — provides a checklist for building owners and managers to help identify if a water management program is needed, examples to help identify where Legionella could grow and spread in a building, and ways to reduce risk the of contamination. The toolkit also includes examples relevant for health-care facilities.

Legionella growth occurs in building water systems that are not managed adequately and where disinfectant levels are low, water is stagnant, or water temperatures are ideal for growth of bacteria, explains CDC.

Facilities managers (FMs) need to know that an effective water management program can limit germ growth by:

- Keeping hot water temperatures high enough;

- Making sure disinfectant amounts are right;

- Keeping water flowing (preventing stagnation);

- Operating and maintaining equipment to prevent slime (biofilm), organic debris, and corrosion; and

- Monitoring factors external to buildings, such as construction, water main breaks, and changes in municipal water quality.

CDC also notes that contaminated water droplets can be spread by:

- Showerheads and sink faucets

- Hydrotherapy equipment, such as jetted therapy baths

- Medical equipment, such as respiratory machines, bronchoscopes, and heater-cooler units

- Ice machines

- Cooling towers (parts of large air-conditioning systems)

- Decorative fountains and water features

CDC put a new measure in place on June 2 to encourage implementation of water management programs. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released a Survey and Certification Memo stating that health-care facilities are expected to develop and adhere to policies and procedures to reduce the risk of Legionella and other waterborne pathogens.

More information about the study is available in the Vital Signs report, which also contains helpful graphics and a video. For more information on Legionella, Legionnaires’ disease, and the CDC toolkit, visit CDC’s Legionella page.