Preparing for an emergency situation is paramount among the responsibilities of a property manager. Evacuating a building, whether a building with 100 occupants or 1,000 occupants, presents numerous challenges for building management. Evacuation strategies often need to be determined within moments, depending on the nature of the emergency. These challenges are often amplified during the evacuation of high-rise office buildings. The strategies listed below can help building management determine which high-rise evacuation procedures to use, depending on varying emergency scenarios.

Defend-in-Place

According to the Fire Protection Handbook, put out by the National Fire Protection Association, defend-in-place (sometimes known as “shelter-in-place”) strategy “recognizes that at times it is safer for occupants to remain in place within protected zones of a building than to evacuate the building.” Such a strategy might be used in the case of a chemical or biological incident, or an explosion, which has occurred outside of a building.

Delayed Evacuation

The Handbook also defines the delayed evacuation strategy as one that “takes advantage of temporary holding places, typically known as an area of refuge or area of rescue assistance, where occupants can remain in relative safety, albeit near the fire area, for a period before evacuating the building, either by themselves or with assistance from emergency responders or others.” Delayed evacuation might be used for occupants with disabilities who are waiting for assistance to help them evacuate.

Evacuation of Individuals with Disabilities

Individuals with temporary or permanent disabilities, or other conditions that would require them to obtain assistance during an evacuation, require special consideration. These individuals who will require assistance from others may include persons confined to wheel-chairs; persons dependent on crutches, canes, walkers, and so on; persons recovering from surgery; pregnant women; persons with significant hearing or sight impairment; extremely overweight persons; elderly persons; children; persons with mental impairments; and persons who may have become incapacitated as a result of the emergency.

A listing of regular building occupants’ names, locations within the building, telephone numbers, type of disability and the names of assigned assistance monitors should be provided ahead of time to building management with the understanding that such information is confidential and is to be used only to facilitate evacuation during emergency conditions. Tenants should be advised of their responsibility of keeping such information current.

The Americans with Disability Act (ADA) definition of an area of rescue assistance is “an area, which has direct access to an exit, where people who are unable to use stairs may remain temporarily in safety to await further instructions or assistance during emergency evacuation.” Once the area of rescue assistance has been reached, assistance monitors and the individual with the disability have two options: (1) dispatch someone to inform the building fire safety director, building management, security, engineers, or—in the case of a fire emergency—the fire department, and await their assistance; or (2) once all occupants have been evacuated from the involved floors and moved past, the assistance monitors may move the individual with the disability to another designated area of refuge inside or outside of the building.

Partial or Zoned Evacuation

Partial or zoned evacuation—also known as “staged evacuation” — is the strategy defined by the Handbook as one that “provides for immediate, general evacuation of the areas of the building nearest the fire incident. A partial evacuation may be appropriate when the building fire protection features assure that occupants away from the evacuation zone will be protected from the effects of the fire for a reasonable time. However, evacuation of additional zones may be necessary.” Once the occupants of the involved floors have been relocated, the decision whether to evacuate them further, using stairwells or elevators, or whether additional floors need to be evacuated, will be determined by building management, the fire safety director, or the fire department.

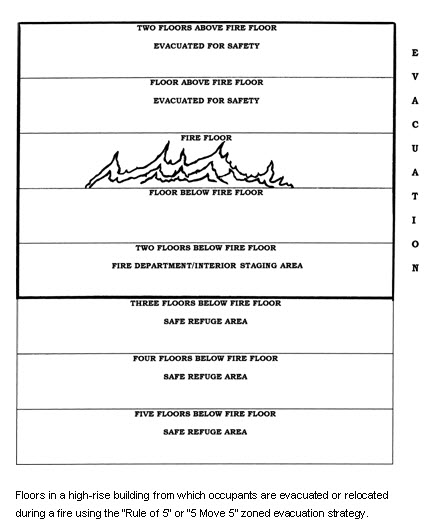

The fire department will usually set the policy for a partial or zoned evacuation. For example, in the city of New York, if a fire occurs in a high-rise building, the fire floor and the floors immediately above are the most critical areas for rapid evacuation. According to Charles Jennings in the J. Applied Fire Science, “in the event that a fire or smoke condition exists, occupants will evacuate at least two floors below the fire floor, re-enter the [building at that] floor, and wait for instructions”; however, in Los Angeles, if a fire occurs in a high-rise building and it is serious enough to evacuate one floor, five floors are evacuated (commonly referred to as the “Rule of 5” or “5 Move 5”): the fire floor, two above it for safety, and two below it (so that the second floor below the fire floor can be used as a staging area for fire department operations). Occupants on these five floors are relocated down five floors thus being relocated to at least three floors from the fire floor; if the fire is on or below a floor that is six floors from street level, the occupants usually will be evacuated from the building. The accompanying diagram shows the floors from which occupants are usually evacuated or relocated during a fire using the “Rule of 5” or “5 Move 5” zoned evacuation.

During a fire situation, it is usually advisable to evacuate downwards in a building. However, if the lower floors or the stairwells are destroyed or untenable because of heat or smoke, only then would it be necessary or more desirable to go to an upper floor or to the building’s roof. The problem with occupants relocating to a building’s roof, particularly in substantial numbers, is its limited space to accommodate people, and the difficulty of evacuating these people, should it be necessary. If the building has a helipad or heliport, as some modern high-rise buildings do, there is not only the problem of obtaining a helicopter, but also of it landing safely to pick up occupants. During serious building fires, air turbulence and updrafts are caused by smoke and heated air.

Total Evacuation

Total evacuation involves the evacuation of all building occupants at once from a building to an outside area of refuge or safety. The size of high-rise buildings, the large number of people often contained in them and the limited accommodation of elevators and stairwells, make it impractical to quickly evacuate all occupants at once. According to the Council on Tall Buildings & Urban Habitat (CTBUH), “sometimes total evacuation can be carried out so that one section of the building after another is evacuated.” This strategy is sometimes known as phased evacuation.

As stated in FacilitiesNet, “in emergencies, [depending on the elevator system] elevators could be programmed to move those with the longest distance to go first. Occupants of lower floors—without disabilities—could choose to use the stairs. During a total evacuation, elevators would collect occupants from the highest floors first, shuttle them to the exit level and return for another load, working their way down from the top. Pressing a call button would register people waiting for pickup but would not alter the sequence, nor would [pressing] the buttons in the elevator car. People with disabilities would not need to be given priority since all occupants would be accommodated equally in this system.”

Such an evacuation would take a considerable period of time, depending on the size of the building and its population at the time, and the nature of the event that caused the evacuation.

Total building evacuation is usually only ordered by the fire department. However, in an extreme emergency, building management or the building fire safety director may decide to totally evacuate the building. Also, in some circumstances, all building occupants might choose to self-evacuate their facility.

Self-evacuation

According to CTBUH, “self-evacuation refers to occupants evacuating by themselves, before emergency responders have arrived on site, using available means of evacuation, i.e. elevators and stairs.”

It is critical that occupant evacuation strategies be clearly defined in a building’s emergency management plan and that all occupants know prior to an emergency occurring that such options are open to them.

About the Author

Geoff Craighead is vice president of High-Rise and Real Estate Security Services with Securitas Services USA. He can be reached at Geoff.Craighead@securitasinc.com.

This article is from High-Rise Security and Fire Life Safety, 3rd ed. by Geoff Craighead (Elsevier, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2009, www.elsevier.com). This book addresses office buildings, hotels, residential and apartment buildings, and mixed-use facilities, and includes a CD-ROM containing a sample building emergency management plan.

Portions of this article were extracted from “Strategies for Occupant Evacuation during Emergencies” by Daniel J. O’Connor, Daniel and Bert Cohen, (Fire Protection Handbook, 20th ed., National Fire Protection Association); Emergency Evacuation Elevator Systems Guideline, Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat); FacilitiesNet, “News: NIST conference to address elevator use in emergencies,” November 2, 2007; “High-Rise Office Building Evacuation Planning: Human Factors versus ‘Cutting Edge’ Technologies,” (J. Applied Fire Science, Vol. 4(4), 1994-95, Baywood Publishing Co., Inc., 1995); and the ADA Accessibility Guidelines for Buildings and Facilities (ADAAG).