by Brady Mick — Communication is an art form and a complex one at that. Whether talking with a customer, family member or a colleague, communication among people boils down to three basic forms: telling, questioning and listening. Of these three, the most important skill for managers to acquire, develop and practice is listening. By understanding the invisible theoretical framework that underlies communication, managers can learn to become better listeners and adopt practices in their work behaviors that lead to more successful communication and fewer breakdowns.

Communication breakdowns

There are several kinds of communication breakdowns that can cause negative, harmful and adversarial interactions among people. These include:

- Societal, such as wars, genocides and extinctions;

- Communal, including issues like inequality, class systems and economic strife;

- Social, such as bullying, prejudice and hate crimes;

- Physical, examples of which include violence, abuse and environmental damage;

- Psychological, such as mental illnesses and intellectual and emotional problems and

- Work, including issues like engagement deficiency, productivity loss and job changes.

In the workplace, it’s important to understand the nature of these breakdowns because with knowledge, managers can gain insight into their employees’ communication limitations. In other words, sometimes there are breakdowns in communication styles. For example, communicators struggling to express themselves through body language or facial expressions could be misinterpreted as aggressive. There can also be breakdowns in thinking, such as when something intended as a suggestion is misinterpreted as a directive. Additionally, sometimes there are breakdowns in emotional intent, such as when what is interpreted as a tone of anger is really coming from a feeling of passion. Even more difficult to address are the challenges that come when the communication expressed means different things to different people.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

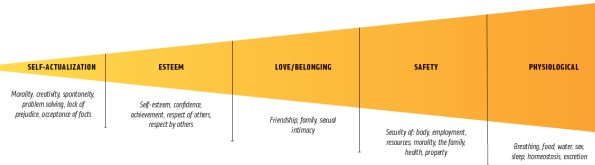

Every individual has a unique set of needs and motivations, and these fundamentals impact communication. In 1943, a psychologist named Abraham Maslow presented a groundbreaking paper on the nature of human needs and motivations. Maslow’s ideas are often presented as a pyramid, with the most basic needs for wellbeing representing the base of the pyramid, and the top level representing personal fulfillment (see Figure 1). According to Maslow’s theory, the most basic needs must be met before an individual will focus on or desire needs at a higher level. For example, if a person is not meeting his basic needs of food and water, he will not be focused on higher level needs such as friendship or gaining the respect of others.

In daily practice, wellbeing is interdependent with all levels of needs. However, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs helps managers understand communication at a deeper level. It enables them to grasp not just what employees are communicating, but why. Employees may communicate about needs that relate to basic physiology (for example, that they are too hot or cold). Or they may voice concerns about safety by asking for extra lighting in the employee parking lot. If they express a desire to help plan a holiday party or team-building activity, employees are indicating their need for belonging. A desire for more office or work space could indicate a need for esteem or even self-actualization by seeking different kinds of spaces to expand creativity, spontaneity or problem solving. Instead of experiencing these requests as complaints or annoyances, managers can connect them to a basic need and understand that the employee is simply (and probably unknowingly) seeking to fulfill an essential need for their work wellbeing.

Communication psychology

Another important aspect of human communication that managers need to grasp relates to the forms of human understanding. The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung identified four ways humans think, feel and experience things:

- Sensation. Humans possess five senses with which they can engage and measure their external reality. These are the familiar senses of sight, hearing, taste, smell and touch.

- Thinking. This is the objective realm of intellect and is expressed as reason or the thought process.

- Feeling. Also known as “the language of the heart,” feeling is expressed as emotion and focuses on value.

- Intuition. This is the “gut feeling.” It’s rooted in ideals of belief, truth, trust and possibility.

According to the theory, a well-rounded person operates in a combination of all four personality functions or types. However, no one develops all four functions equally. Every individual has one dominant type and at least one lesser-developed, or unconscious, type. By understanding how people experience their communication engagement, managers can recognize how employees perceive information and make decisions. For example, intuitive types may not have the same linear, organized and detailed work style as those employees with a stronger thinking type. The intuitive employee is more likely to “investigate” when speaking and approaches problems and projects from multiple angles. A logical, lineal thinker may become frustrated with such communication.

Communication styles

The third theoretical framework for managers to consider is styles of communication. These include:

- Words. As the most commonly understood form of communication, words have evolved into complex forms, both written and spoken.

- Gestures. Equal in importance to words, gestures have had equal study in communications between humans, as well as extending into the animal kingdom.

- Expressions. The nonverbal transference process in communication, expressions are dependent on the sensory form of understanding.

- Intonation. A deeper, more subtle and powerful expression of communication, intonation is based on the sound quality and intensity of words and gestures.

- Introspective. Autonomy is the venue of the highest forms of communication and becomes the “meaning” of the individual’s unconscious. It is the realm of the artist, the poet, the designer, the scientist and the philosopher.

Managers need to understand that every communication style is unique. Understanding the influence of the styles depends upon situation and often takes great effort. For example, a manager may hear the words of an employee expressing concerns over a complex work problem to be solved. If the manager’s expressions communicate primarily caring and consoling, this may erode the motivation and frustrate the employee. Why? The employee may have been trying to communicate his or her introspective struggle in a search for help instead of consultation. The misalignment was likely in the misinterpretation of the employee’s intonation.

Why breakdowns happen

The practical application of studying communication among people at work involves acknowledging the complexity of the conditions surrounding communication. First, what is the hierarchical purpose of the communication? Does it express a need, want, desire, goal, aspiration or any combination of these? Second, how is the understanding of the communication intended to travel from one person to another: is the delivery sensory, intellectual, emotive or intuitive (or a combination thereof), and through what function(s) is it absorbed? Third, what form of communication is used? Is the form word-based, physically gestured, symbolically expressed, emotively intoned, actualized via artistic extremes or some combination of forms?

Day-to-day tactics

Communication tactics can be learned. As managers answer the questions above, they can apply day-today practices focused around listening to increase the efficiency, effectiveness and experience of their communication with employees, peers, superiors and even clients. The following are six key behaviors that managers can practice to improve listening skills:

- Expand expectations for solving business problems. Because it’s clear that communication is a very complex process, and not the straightforward, cut-and-dried activity often expected, the approach needs to change. Understand that some problems or situations will now take longer to resolve because certain types of communication have to take place as the complexity of business problems impacts people.

- Don’t be an order taker/giver. It is important for managers to listen before telling in order to communicate with team members and understand their insights. Most companies want engaged people, not servants. When a client says “Give me this on this date,” and a better solution is apparent, managers shouldn’t hesitate to consider ideas that make the problem easier to define and solutions of higher quality.

- Think creatively. Creative thinking requires the suspension of directive questioning and thrives when inquisitive questioning is followed by intensive listening. Managers who expand their thinking and do not rely solely on solutions of the past produce better results. With increased listening skills, it becomes possible to connect to an employee’s desire for esteem and self-actualization and achieve new and innovative business results.

- Be curious. Good managers ask questions that avoid a “yes or no” response. They seek stories first and, above all, seek to understand the meaning of the employee. When managers first seek to understand the meaning of the communication from an employee or customer, they will be better positioned to fill the need.

- Become proactive. Managers need to reverse the fire-drill model of communication. Instead of waiting for a frantic business problem or for a deadline with nowhere to turn, proactively check in with teammates periodically and listen to the insights and ideas.

- Redefine value. The value of communication is complex and requires time and commitment to attain high value and performance. Develop and use a higher quality of communication that is listening based. Use all forms of communication consciously and often. Good communication takes time.

Implications for design

Often the space in which we work is limited in its ability to facilitate all forms of communication. While it’s ideal that workspaces are built with the vitality of listening-based communication in mind, there are ways to adapt spaces to meet the desired behaviors of listening. For example, reposition closed doors — not just physically, but metaphorically as well. While open doors can facilitate day-to-day communication, a closed door can meet an employee’s need for safety if they have a serious problem to discuss with a manager.

While it may not be possible to change the physical structure of the workplace, managers can create spaces that facilitate listening. Whatever form these take — conference rooms, alcoves in a cafeteria or even a room dedicated to teleconferences and webinar viewing — find spaces that allow an individual or group to listen with focus and intent to the communication of others.

Workplaces that create spaces that address Maslow’s hierarchy of needs have a distinct advantage. Even the bottom level of needs — food, air and water — can be addressed with an inviting community room. If people are communicating a desire for greater self actualization in their work, seek white boards or shared screens to display ideas and encourage higher forms of communication.

Listen first to avoid communication breakdowns

How powerful is listening as a form of communication? The answer: so powerful it’s considered a tool in the fight against mental illness. A problem that many people experience today is anxiety disorders. When sufferers of chronic anxiety have a panic attack, their ability to listen and reason shuts down. Parents, spouses, coworkers or managers, wishing to help the victim through their struggles, may instinctively start telling the victim what to do. For example, they may say things like “Just calm down,” or other well intended but ultimately harmful admonitions.

Alternatively, in a struggle to understand the victim’s condition, their instinct may be to ask him or her too many questions: “Why are you so upset?” “What’s wrong?” “Don’t you see you’re being silly?” What doctors have learned is that sufferers of anxiety disorders recover more quickly when friends, family and coworkers close their mouths and open their ears.

The Anxiety and Depression Association of America list several ways to help anxiety sufferers on their website (www.adaa.org) that drive home the point of listening. For example, their advice for parents of college-aged anxiety sufferers includes, “Be an active listener. Lend an open ear when your child is feeling stressed or overwhelmed. Listen to what he or she says, as well as to what isn’t said. (Is there any mention of friends or social activities?) Respect his or her feelings even if you don’t fully understand. This will encourage your child to start talking, which can serve as a source of comfort when feeling overwhelmed.”

Say less, listen more

If simply listening can be a powerful tool to aid those with mental illness, what can it do in an office environment in which the goal is simply to communicate well? Unfortunately, most management is built on telling, and in some cases the process of inquiry, i.e., to question. But where many fall short is in the area of listening. When professionals aren’t skilled listeners, the result is a breakdown in communication, resulting in a workplace that falls short of achieving the richness of results for people and their companies. FMJ

Brady Mick is client leader with BHDP Architecture. He provides design expertise in strategic design, culture, social dynamics, work process and change alignment. For more information, visit bhdp.com or call +1-513-271-1634.